By Alexandra Kiritsy and Andrew Jendrzejewski

Our biggest goal with “Yiayia & Me” is to spark curiosity in family history among Greeks. We simply hope to inspire individuals to spend time with their ancestors–of both the past and present–by learning about their stories. Thus, when Andrew Jendrzejewski told Greg and I that our blog had inspired him to learn more about his own yiayia from Samos, we were incredibly excited and happy! Hence, for this week’s post, we would like to share Andrew’s adventures and discoveries as he uncovered his own family history!

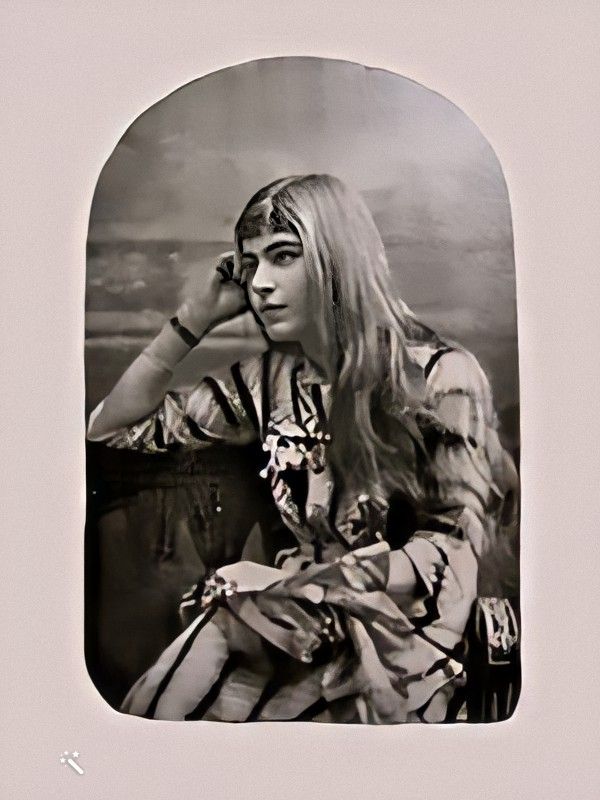

Andrew and his family had heard one compelling, yet curious story about his yiayia’s home in Samos. His yiayia, named Aikaterini Logara, was born in 1897 in present-day Ampelos, Samos, and her story was as follows: ‘Pirates’ had come to Samos. The villagers hid their young children, especially the girls, in a secret cave on Ampelos Mountain. When the coast was clear, they sewed her [Aikaterini] up in a mattress and smuggled her down the mountain to a boat (probably in Karlovasi), which took her to her older sister, Eirini, and her husband Georgios Youroukelis (Giouroukelis), who waited for her in Alexandria, Egypt, where she would grow up.”

Part of an 1856 Map of the Aegean, © Greek Ancestry Maps Collection

As Andrew said, this story was, of course, quite fascinating to him as a child, and it remained so even into the present. Therefore, this tale served as a great hook for him to dive into his own family history as well as the local history of Samos. He decided to feed the history books a family legend, and the books were able to help him unpack the kernel of truth in it. In the end, he was able to paint a more vivid portrait of the birthplace of his beloved Yiayia.

Now for Andrew’s discoveries about Samos and the world at the time his Yiayia was born, which ultimately help to inform her pirate legend…

While Samos was meant to be sovereign internally, a prince was chosen by the Ottoman Sultan to act as governor of the island. Each governor, Ottoman Turk or Greek, generally overstepped their function by being unjust and cruel–often overriding Samos’s Parliament. However, in the Parliament, there were also Pro-Ottoman (Conservative) Greeks, who perhaps did not want to rock the boat with the Empire or even felt more akin to the Ottoman or Anatolian Greeks there. But Anti-Ottomans in Parliament, who were fiercely Pro-Hellenic (Progressive), were upset that Europeans in 1835 drew the boundary between Greece and Turkey to bind them to the Ottomans. They felt that Samos’ efforts during Greece’s War of Independence (1821 – 1830) earned their right to be included with Greece, not the enemy that they had sacrificed so many lives to fight. The feelings of both groups persisted into the twentieth century.

Crete, which was cut away from Greece by the European powers after the War of Greek Independence, inspired the Samians with their own revolution against Turkish dominance. Just two years before Yiayia was born, the Cretans revolted. In 1897, the year Yiayia was born, the Greek Turkish War started. These events inspired Pro-Greek people on Samos.

What followed explains what led up to Samos’s unification with Greece, and it also explains Yiayia’s story. From the time Yiayia was born to the time she evacuated from the island as a ten-year-old, many different Princes were appointed by Sultan Abdul Hamid II to govern Samos. Reading about them explains the state of Samos in those days and provides a foundation for Yiayia’s story:

Stefanos Mousouros (1896 – 1899) built a road from Vathy to Mytilinioi but was viewed as unjust by the Samos people.

Konstantinos Vagiannis (1899-1900) was initially on very good terms with the Samians. Unrest grew, however, when he forbid the Samian anthem and flag and fired Samos’s mayor. When he also attempted to restrict people’s rights, the Parliament requested his replacement and the Sultan agreed.

Michail Grigoriadis (1900 -1902), who succeeded Vagiannis, was so incompetent that the President of the Parliament was effectively the Prime Minister of the Island, so he was dismissed from his post.

Alexandros Mavrogenis (1902-1904), an Ottoman Bey from an important family ruled strictly, but was intimidated by the quarreling Greek parties in Parliament.

Ioannis Vithynos (1904-1906), an Ottoman Greek, wrote articles for Turkish publications and notably wrote comments on the Ottoman Commercial Code. He served as Governor of Crete (1868-1875), taught at an Ottoman Law School, and served in the Ottoman Ministry of Justice and Tribunal as a Judge before he came to Samos. By the time Vithynos became Prince of Samos, there was already much political agitation, and it kept building. The Conservative faction led by one Ioannis Chatzigiannis of the Parliament was pro-Ottoman. Like his predecessors, Vithynos chose to side with the Conservative party under which crime was rampant. Embezzlements, theft, murders, revenge, censorship in the press, crooked elections and violence in general continued to be commonplace. In 1906, a newly elected Senate blamed Vithynos for these problems, so he was unseated.

Kostakis Karatheodoris (1906-1907), an Anatolian Greek Statesman and member of a distinguished Phanariote Karatheodoris family replaced Vithynos. Kostakis’s older brother, Alexandros, served as Prince of Samos for ten years (1885 – 1895). Kostakis studied engineering in Europe, managed the Ottoman Railways, served on the Supreme Council of the Ottoman Empire and built a major road connecting the cities of Vathy, Karlovasi, Marathokampos, Platinos, Pyrgos and Chora, Samos’s former capital under Prince Miliades Aristachis (1859 – 1866). This was materially good for Samos, but while Kostakis was Prince of Samos, the Patriotic (Conservative) and the Progressive (Liberal) Parties began arguing over the efforts of the Progressives to establish a Greek Bank on Samos. The Conservatives resisted this anti-Ottoman move. In his attempt to resolve the quarrel, Kostakis consulted the Sultan who was annoyed at both the Samians and the Prince’s indecision. The Pasha signed a note of permission, but the note was valid only if Kostakis also signed it.

In 1907, the Prince’s indecision might have given the opportunity for Yiayia to leave the island; she would have been 10 years old. However, were times volatile enough then to have smuggled her to the ship sewed up in a mattress? Her baptismal record says that she was born in 1897, but I remember being told that she was born in 1898, so her memory does not seem to have been clear. Thus, perhaps there was another time when the story seems to fit better. So, the historical adventure continues:

Prince Karatheodoris apparently thought he would please the Sultan by signing the note; he did, but that resulted in the sultan removing him from the position.

Georgios Georgiadis (1907) was appointed in September 1907, however, as he started firing and appointing clerks at will, he was removed after a couple of months.

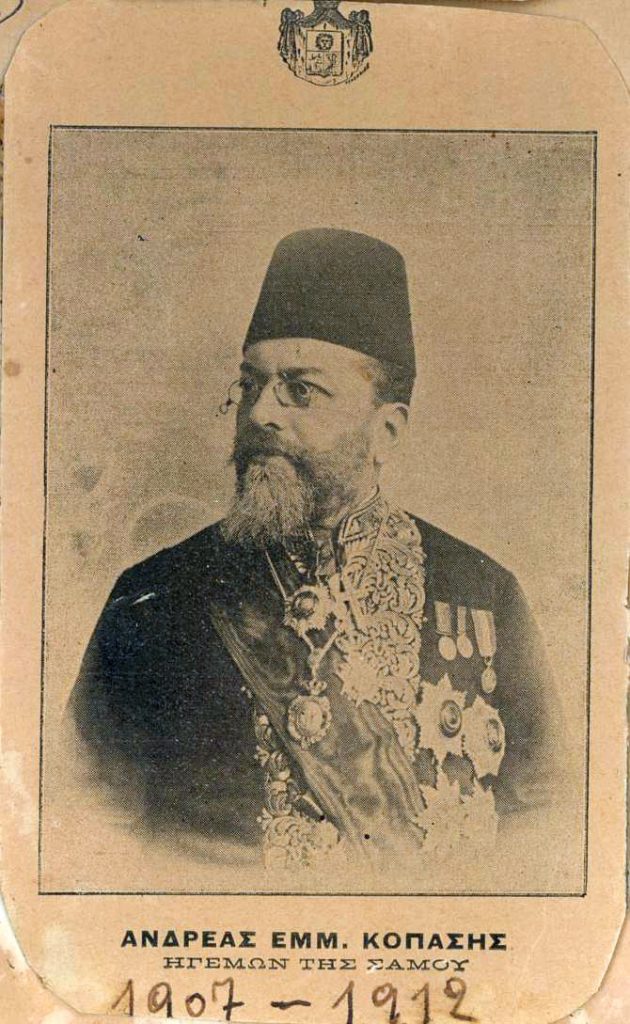

Andreas Kopasis (1908-1912), replacing Georgiadis was a vicious “tyrant,” who brought Turkish Soldiers onto the island in May of 1908 as the campaigns for the fall parliamentary elections were heating up. Kopasis protected his status and quelled the activities of the Progressive party with violence, murders, imprisonment and censorship, all of which made the Progressive Party take more aggressive actions as insurgents. This escalation of violence and insurgency between the factions seems to give a definite reason for hiding all the young girls in a secret cave. The Turkish Army and the more intense fighting during the summer of 1908 seems to fit more clearly with Yiayia’s story.

In the elections of Fall 1908, a seasoned progressive politician, Themistoklis Sofoulis, was elected to lead the Parliament and became the leader of the Progressive Party. Sofoulis completely replaced as many people throughout the government as he could, he completely overhauled the entire Gendarmery. He made it appear that he had become a despot and won favor with the new Prince Kopasis. Kopasis was so happy that he held New Year celebrations with three battleships in Vathy Bay. However, Sofoulis had ordered two torpedo boats to block the mouth of the bay to face-off those three battleships. In the meantime, Sofoulis and about 60 other statesmen and citizens fled to Athens for safety.

This might be the time period to which my Yiayia referred when they were “invaded by pirates.” She likely meant the Turkish soldiers. Perhaps adults might have used that language for the children, who were certainly too young to fully understand what was happening. By being “hidden in a secret cave on Ampelos mountain until the coast was clear,” not only implies the fact of Turkish suppression, but also denotes a definite pause in violence, as Sofoulis orchestrated his trick on the Prince. I believe that late fall or early winter of 1908, or very early in 1909, was when villagers evacuated my Yiayia, Aikaterini, in a mattress past Turkish soldiers to a boat in the nearby harbor of Karlovasi–sending her to Alexandria, Egypt, perhaps via Athens.

Kopasis was eventually assassinated. A young editor for “Progress”, a Karlovasi Newspaper, in his 20’s took the leadership position in the Parliament for two months, before Sofoulis was elected President after returning from Athens. By 1912, he won the unification with Greece and the return of the Ottomans to their homeland.

By then, Yiayia would have been in her teens living with her older, married sister, Irene, her husband, Georgios Youkourelis (Giouroukelis), as well as their four children. She never resided on Samos again although she visited occasionally. My childhood must have seemed so protected, soft, safe and trivial as she waved that slipper at us, scolding in Greek, especially when compared to her childhood memories laden with fear, violence, hiding. The word «Σιώπα!» “Quiet!” meant a world of difference to us than it may have meant for her.

Thank you for reading!

Share your story or consider making a donation by clicking here, and make your yiayia proud!