When doing genealogy research, we always come across information that we do not know how to interpret, and new questions pop up in our heads. We find a birth record and automatically ask ourselves “how many children were born in this village in that year?” or “how many children of his age were there when my pappou was growing up?” When we find marriage records, we cannot but wonder “At what age did people usually get married?” or “How many people would have a second or third marriage?” Based on original research and statistical analysis, this article will attempt to shed light on questions that have to do with a relevant, but rather ghoulish topic: death. Along with statistics and numbers, unusual causes of death will also be presented. The island of Samos, and specifically the village of Kontakeika, will serve as our case study.

About Kontakeika

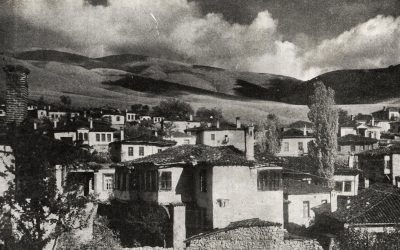

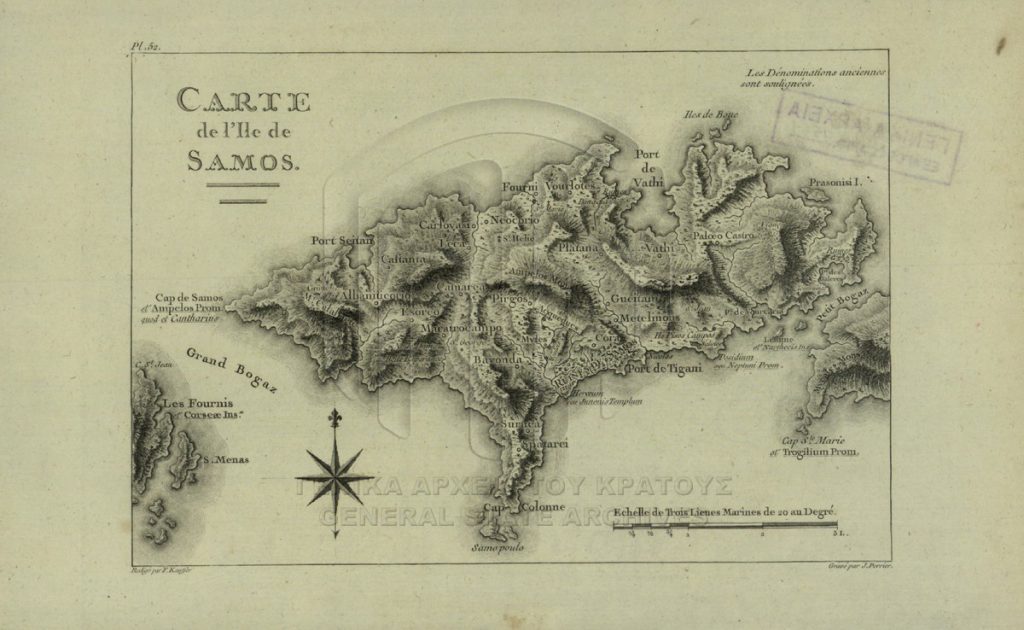

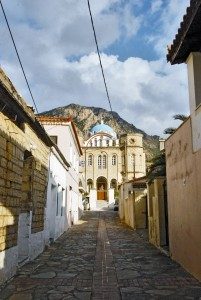

The village of Kontakeika is located in the northwestern part of Samos Island, 28 km from the island’s capital, Vathy, and 5km from the port town of Karlovasi. The village is built on the northwestern foothills of Mount Karvouni.

The settlement and establishment of communities in Kontakeika, as well as on the island of Samos in general, has a long historical background. Continuous raids by Arab and Ottoman pirates had a dramatic impact on life on the island.Notably, after the mid-15th century, the island was essentially abandoned, and the majority of the population sought safety in the neighboring coasts of Asia Minor, as well as in Lesbos and Chios. The few locals who decided to remain in Samos isolated themselves in remote, mountainous areas away from the sea to avoid becoming targets of attacks. Fortifications were built in high locations to provide refuge for the inhabitants and to protect them from pirates; the village of Kontakeika is no exception, as it also had a castle with tall walls and lookout posts constantly watching out for enemy movements on the horizon. After the mid-16th century, a new policy of the Ottoman Empire regarding settlement in the Aegean, brought back descendants of the old residents as well as Christians from other parts of Greece.

Regarding the name “Kontakeika”, the question of its origin divides scholars. On one hand, Emmanouil Kritikidis, believed that the name came from the village’s first settler, Georgios Kontakis, a Peloponnesian who, along with his compatriots, purchased large tracts of land in the area in the early 18th century. On the other hand, Epameinondas Stamatialis refers to a Georgios from Kos as the first settler, who had the nickname “Kotis” due to his origin. In the mid-18th century, he bought large areas of land and subsequently expanded through the marriages of his children with the neighboring village of Ydrousa, thus establishing a new village in response to the growth of the settlement.

According to the last census in 2021, the population of Kontakeika is 1,076 residents. Of course, the demographic picture presents fluctuations over time, with the peak population of the village occurring in 1940 (1,464 residents). Previous censuses provide the following figures: 1869 – 611 residents, 1886 – 806 residents, 1940 – 1,464 residents, 1991 – 888 residents, 2001 – 904 residents, 2011 – 940 residents.

Statistics

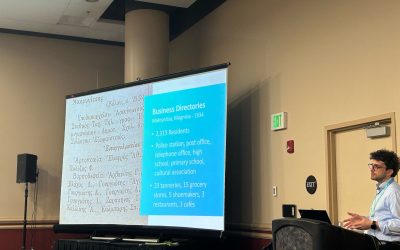

After a thorough analysis of all the civil vital records of Kontakeika from 1855 through 1932, which are preserved at Samos’s General State Archives office, we have gathered and analyzed a wealth of information about the population of the village. The following statistics are the product of this analysis. As this article focuses on death statistics, birth and marriage statistics will be presented without long detailing and analysis.

Birth Statistics

From 1855 to 1932, the births of a total of 1,498 boys and 1,380 girls were recorded by the village’s Town Hall. While some births might have gone unrecorded, these numbers should be generally considered reliable, as the village’s authorities seemed to be quite meticulous in record-keeping. Apart from the total number of births, the timing of births was also interesting. The months with the highest births were January (350 births) with a rate of 12.17%, December (252 births) with a rate of 8.76%, and October (251 births) with a rate of 8.72%. The months with the lowest births were June (218) with a rate of 7.58%, November (217) with a rate of 7.54% and September (195 births) with a rate of 6.78%.

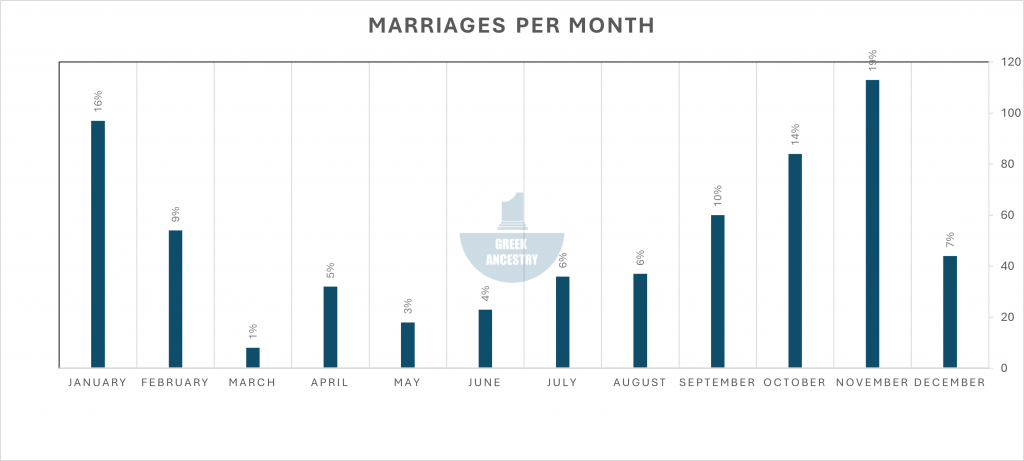

Marriage Statistics

One notable detail we glean from the records is that from 1855 to 1932 there were 606 marriages in the village. In the 551 marriages that recorded the marriage degree, men had 498 first (A), 52 second (B), and 1 third (C) marriages, while women had 508 first (A), 41 second (B), and 2 third (C) marriages. While according to this data men had second marriages more often than women, the number difference and our sample are considered too small for conclusions to be drawn. In the 173 marriages where age was recorded, the average age of men was 26 years, while for women, it was 22 years.

Death Statistics

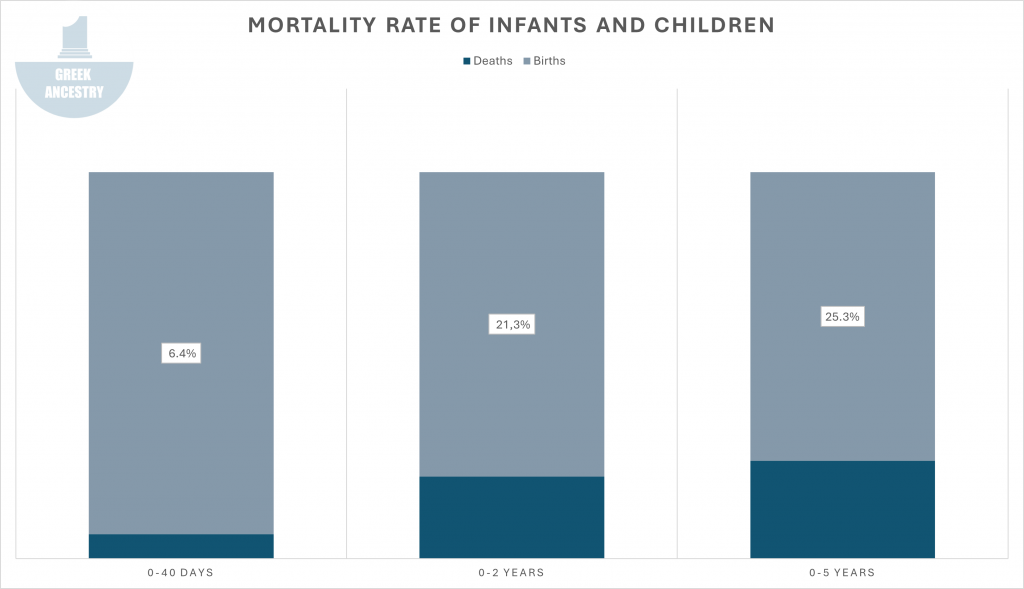

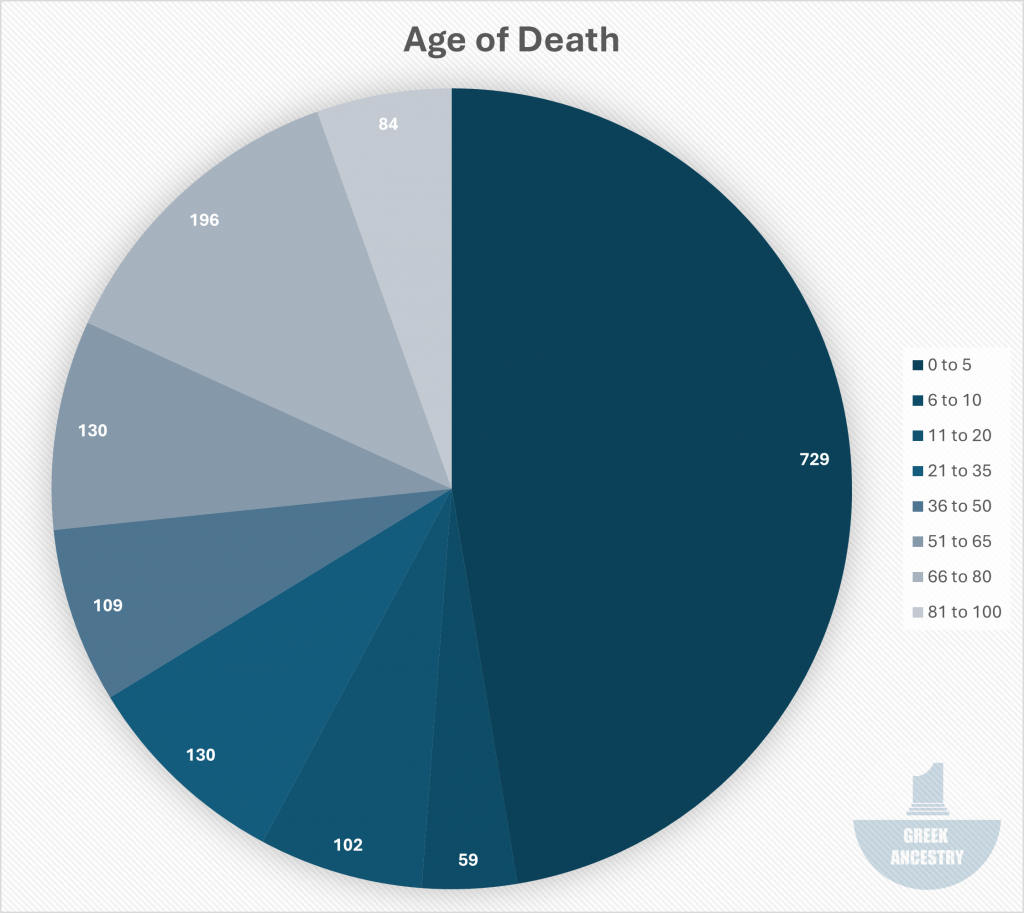

Apart from the joyful events of the village, such as births and marriages, we also came across a more morbid side of everyday life in Kontakeika through the detailed recording of deaths over the years. These grim statistics show a total of 1,551 deaths from 1855 to 1932, or an average of 20 deaths per year. Of these, 1539 certificates included the age of the deceased. Among these, we notice 183 deaths of infants (up to 40 days old), 612 child deaths from ages 0 to 2 years, and 729 child deaths from ages 0 to 5 years. In other words, if we compare these numbers with those of births, a child that was born had 6.4% chances of dying before reaching the age of 40 days, 21.3% chances to not reach the age of 2 years, and 25.3% chances to die before the age of 5. Apparently, after reaching the age of 2, children had higher chances of living.

We counted 59 deaths from ages 6 to 10 years, 102 deaths from ages 11 to 20 years, 130 deaths from ages 21 to 35 years, 109 deaths from ages 36 to 50 years, 130 deaths from ages 51 to 65 years, 196 deaths from ages 66 to 80 years, 84 deaths from ages 81 to 100 years, and 30 deaths from ages 90 to 100. The average age of death for those between 1 and 100 years old, was calculated at 36.7 years. The average age for those between 6 and 100, was 49.5 years. These numbers indicate that as long as someone reached the age of 2, from then on, they had high chances of living through the age of 50. Then, the downfall started. Of those who made it to adulthood (ca. 20 years old), most people (48%) would not grow older than 65 years. Only a 4.6% of adults would make it into their 90s.

As for the timing of deaths, most of them apparently occured in July (156) with a rate of 10.06%, in August (146) with a rate of 9.41%, and in November (143) with a rate of 9.22%. The least deaths occurred in April and October (120) with a rate of 7.74%, in June with a rate of 6.32% and in May (85) with a rate of 5.48%.

(Unusual) Causes of Death

Statistics offer interesting hints into life expectancy and mortality rates in the society of Kontakeika. However, apart from the inferred statistics, additional information can be found in the village’s death certificates, especially when it comes to causes of death. In many cases, especially when the death was not caused by natural, usual causes, the registrar included the deceased’s cause of death in the records, sometimes with more and some times with less details. In any case, through our research, we encountered details of events that undoubtedly disrupted and altered the lives of the residents of Kontakeika. These events vary and touch upon a wide range of causes and factors that certainly cannot be accurately detailed in a death certificate. However, we can be certain of the sorrow and pain they caused to the relatives and friends of the deceased. Below, we will elaborate on some of these cases. Some of them may pertain to unusual events, while others may refer to particularly significant diseases that brought turmoil to the lives of this small community.

War

WWI (aka the Great War) did not leave the small village of Kontakeika untouched. Konstantinos Tsipnis son of Diamantis, a soldier of the second artillery battery, was wounded and transported to the Greek Red Cross Hospital in Thessaloniki on September 10, 1918. Ten days he succumbed to his wounds. On October 10, 1918, the news of his death arrived at the village through a letter to the Registrar. He informed the deceased’s family and composed the corresponding death certificate.

Disease

One death certificate we discovered concerned the death of a farmer from rabies. In 1856, young Georgios Argeras, son of Manouil and Grammatiki, was infected and died from the rabies virus. Rabies, a viral disease of the central nervous system, is transmitted to animals and humans through bites or contact with the saliva or injured skin of rabid animals. In the past, this disease was particularly known and prevalent in agricultural communities.

Another common disease was tuberculosis. In 1927, 24-year-old Iraklis Markos, son of Ilias, died of phthisis, according to the Registrar’s note on the death certificate. Sadly, that was not a unique case. Several other tuberculosis deaths were found in the Kontakeika records from that time period. Phthisis or tuberculosis plagued in Greece in the early 20th century, until the first medications to combat the disease were developed in 1952. Numbers are indicative: 35,000-40,000 patients aged 18-40 died of tuberculosis every year. By 1930, the country had lost 1,000,000 people due to the disease. Tuberculosis typically affects the lungs but can also impact other parts of the body and is easily transmitted when infected individuals cough, sneeze or transmit their saliva through the air. The scientific medical community of Greece was called to confront this threatening and contagious disease, establishing numerous sanatoria and specialized clinics to address it.

Murders & Suicides

Certainly, apart from major historical events and the epidemic diseases of the time, the Kontakeika vital records reveal that the village harbored its own macabre and secret stories. Murders and suicides were not common, but did happen in Greek villages, undoubtedly causing turmoil and fear.

On September 29, 1903, a 23-year-old farmer, Antonios Antoniou was found murdered. “Murder” (φόνος) was the word used by the Registrar, however, no further information was provided about the perpetrator, the motive and circumstances. Communication with the Archives of Samos and the local Police Department offered no additional details. But animosities and conflicts present in a small community could result in bloody events. And, of course, when circumstances were not examined well enough, it is not impossible that murders could pass as suicides. On June 9, 1896, Fr. Georgios Papanikolaou informed the Registrar of Kontakeika that 45-year-old farmer Dimitrios Konstantis was found dead on the beach of Karlovasi. His body was spotted at a location called Peristerofolia. Dimitrios had drowned and the incident was recorded as a suicide. A more clear suicidal case was that of 33-year-old Ioannis Charitou, resident of the village and farmer, who took his own life on April 24, 1879, and was found hung.

Almost a year and a half after the shock of Dimitrios Konstantis’s death, and just a few days before Christmas of 1897, another unfortunate incident took place in Kontakeika. 47-year-old Grammatiki, wife of Dimitrios Anastasiou was found dead at the Saint Nicholas port. Following an examination and investigation by the police officer of Karlovasi and a corresponding medical report, it was concluded that it was a suicide, thereby eliminating the possibility of murder. The medical report mentioned that Grammatiki “suffered from her mind” (Gr. “έπασχε τας φρένας”) indicating she had some psychiatric disorder. Of course, no further details were provided, which may be attributed to the limited understanding regarding mental health issues back in 19th century Greece.

***

Statistical analysis can be a useful tool in genealogy research and enables us to answer a variety of research questions. Most importantly, it allows us to build context around our findings and therefore understand them better. In this case, spooky statistics were combined with sad and unfortunate stories to shed light on a less-discussed aspect of our ancestors’ everyday life: death.

About the Authors

Christos Kerasidis is an archivist, graduate of the Ionian University. He works at Greek Ancestry as an archivist and indexer of historical collections.

Dimitris Kourmpatsos is a history student at the University of Athens. He is currently an intern at Greek Ancestry.