July 24th, 2023, marked the centennial of the Treaty of Lausanne. This article aims to shed light on the historical context of that Treaty by studying newly digitized records of Greek refugees from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace. The findings of the statistical analysis will enable us to visualize the geographical origins of the refugees and gain a deeper understanding of the history of Hellenism in Asia Minor.

The Treaty of Lausanne and the Population Exchange

After a prolonged period of war in the Balkans and Asia Minor, which included the Balkan Wars and World War I, and following the Greek army’s defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922), Greece and Turkey decided to put an end to hostilities and initiate peace negotiations. On July 24th, 1923, after almost eight months of deliberation, the status of the relationship between the two countries was finally settled within the framework of the Treaty of Lausanne. This Treaty was agreed upon by the World War I Allies (French Republic, British Empire, Kingdom of Italy, Empire of Japan, Kingdom of Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, and the Kingdom of Romania) and Turkey. The Treaty of Lausanne not only resolved territorial disputes between Greece and Turkey but also aimed to prevent future conflicts through a special population exchange agreement.

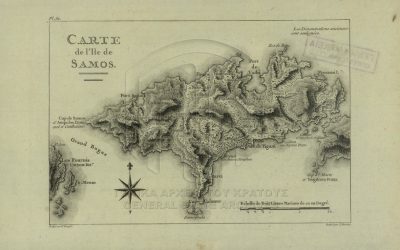

Greek populations had been living along the coasts and inland areas of Turkey since ancient times. During the 19th century, these populations increased, particularly along the western and northern coastlines, with Greek communities flourishing in cities such as Smyrna, fostering economic activity and culture. Following the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922), the fate of the remaining populations became uncertain, while solutions were also needed for those who had hastily left the country during the conflicts. Simultaneously, Muslim populations continued to reside in Crete, Epirus, Thessaly, and predominantly Macedonia. Therefore, as part of the negotiations in Lausanne, the two countries agreed on a population exchange plan, affecting approximately two million people, including 1.5 million Greeks and 0.5 million Muslims.

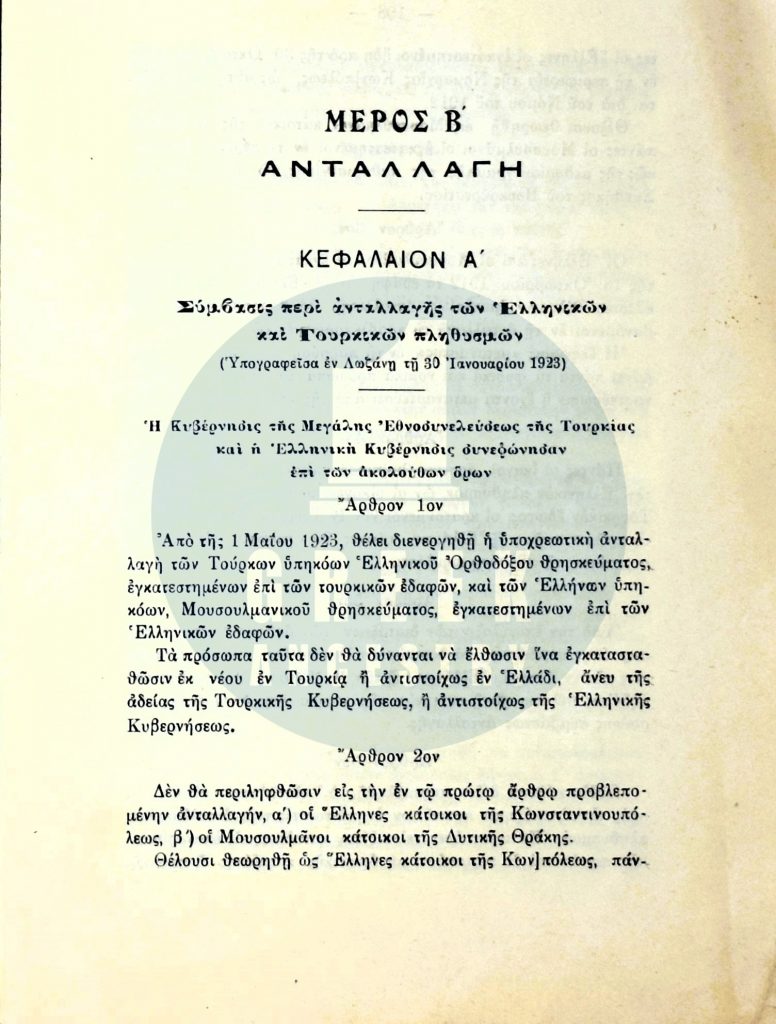

The “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations” was signed on January 30th, 1923, and was subsequently ratified by the Treaty of Lausanne. This marked the first instance in history of a large-scale mandatory population exchange being organized. The exchange was based on the assumption that people of different ethnic and religious backgrounds could not coexist peacefully, and that separating them was the only solution to prevent future conflicts. Beginning on May 1st, 1923, Greek Orthodox residents of Turkey were required to abandon their lands and relocate to Greece, while Muslims in Greece had to move to Turkey. Certain populations, such as the Greek communities of Constantinople, Imbros, and Tenedos, as well as the Muslim population of Western Thrace, were exempted from the agreement.

Property, compensation and settlement

According to the Convention, refugees were allowed to bring their personal belongings with them. Meanwhile, the Greek State made the decision to compensate them for the immovable property they were forced to leave behind. Commissions and organizations were established to facilitate the migration, settlement, and compensation process. Greek refugees were given the option to choose between a rural or urban compensation plan. The “rural plan” included land, animals, seeds, tools, and accommodation, while the “urban plan” offered financial compensation based on the property the Greek refugees had left in Turkey, along with accommodation.

In 1924, the Exchange Directorate was established under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Agriculture to assess the refugee properties left in Turkey. Special committees were formed to oversee this massive project, with each refugee group having its own committee comprised of locals. Unfortunately, refugees who opted for the urban compensation plan were never fully compensated for the properties they had to abandon in Turkey. The Greek State simply did not have sufficient funds to provide adequate compensation, and the size of the properties presented further challenges. Additionally, Turkey’s lack of cooperation complicated the situation, and evaluating the properties left behind in Asia Minor proved to be a difficult and time-consuming process.

Furthermore, the population exchange was not a one-time event but rather a protracted process that continued for years after its official implementation. The exchange was far from smooth and posed significant hardships for the refugees, who had to leave behind their homes, businesses, and communities and start anew in a foreign land with limited or no resources. Many refugees faced considerable difficulties in adapting to their new environment and integrating into their host societies. Some even encountered discrimination and hostility from their fellow citizens, exacerbating their already challenging circumstances.

Despite these challenges, the population exchange did have some positive outcomes. For instance, it helped to create more homogeneous populations in both Greece and Turkey, reducing the potential for interethnic and interreligious conflicts. It also contributed to the development of new settlements and the modernization of agriculture in rural areas. Additionally, many Greek refugees possessed valuable skills as artisans, merchants, and professionals, thereby making significant contributions to the local economy and culture.

The Archives of the Evaluative Committees

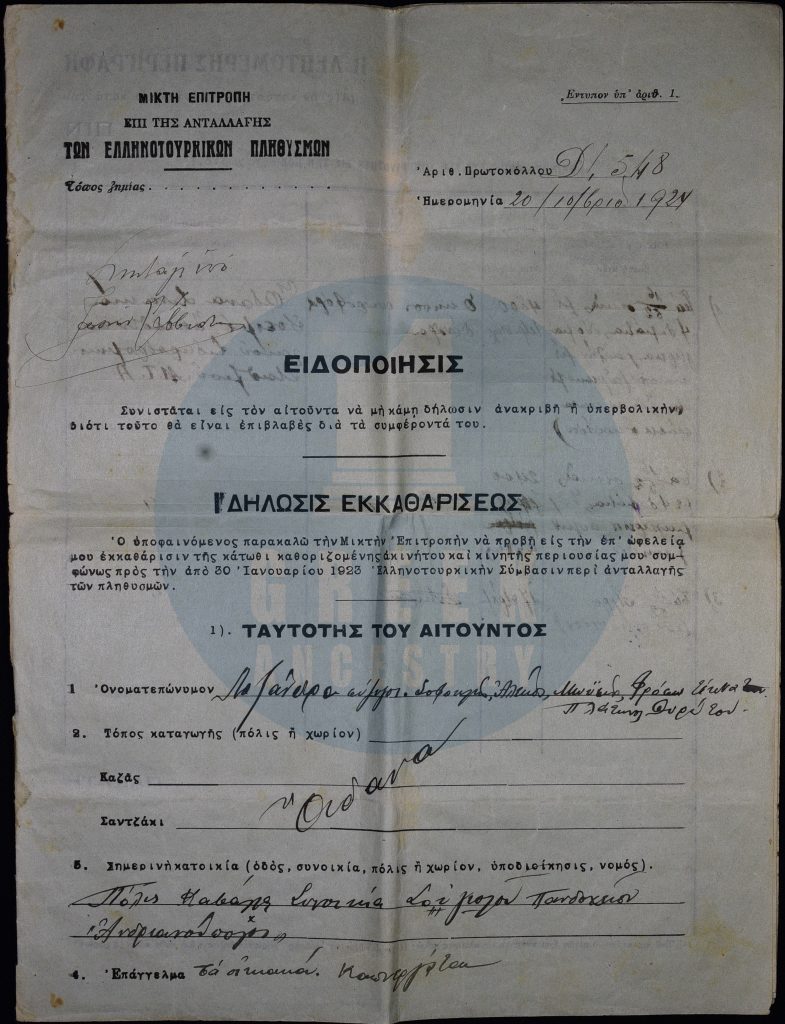

In May 1924, the General Directorate of Population Exchange was established within the Ministry of Agriculture with the purpose of gathering information about the properties owned by Greek refugees. The regions where Greeks resided prior to the Treaty of Lausanne were divided into ecclesiastical provinces (e.g., Amaseia, Efesos, Ikonio, Prousa, Smyrna, etc.), and each province was further divided into communities (e.g., the community of Fokaia in the province of Smyrna). An Evaluation Committee was established for each of these communities and was based in the areas where refugees from that specific community had resettled.

Each Evaluation Committee consisted of four members. Three of them were distinguished individuals from the community under examination, while the fourth member served as a secretary and was appointed by the Ministry of Agriculture. The Committee was responsible for collecting applications from refugees, examining their financial claims regarding both movable and immovable property, and determining the amount of compensation based on the personal knowledge and understanding of its members, as well as received information.

The valuation of properties was conducted in Ottoman gold liras, and the amount of compensation was usually smaller than the requested sum. The committee had already established minimum compensation amounts for specific types of property. For example, a house was valued at 100 Ottoman gold liras or more, while a horse was valued at 10 liras. This documentation constitutes a valuable source of information regarding the economic and social status of the refugees before 1922, when they were still in their homeland. As expected, significant variations can be observed depending on whether the community was an urban center or a small village in the hinterland, as well as whether it was located on the coast or in the mountains.

For instance, in the parish of Agia Foteini in Smyrna, property declarations included shops selling clocks, eyewear, silk, fabrics (such as velvet, fur, and hats), hunting supplies, and porcelain. In the parish of Agios Grigorios in Trebizond, compensation claims were made for ironmongeries, paint shops, and goldsmiths. On the other hand, documents concerning the communities of the Kars province, which were primarily involved in agriculture and animal husbandry, mentioned meadows, pastures, threshing floors, and agricultural tools. In coastal areas, declarations mentioned fishing boats, nets, and sailboats. Similar variations can be observed in agricultural production, with olive trees, cotton, and vines predominating in the coastal areas of Asia Minor.

The Digitization of the Refugee Registers

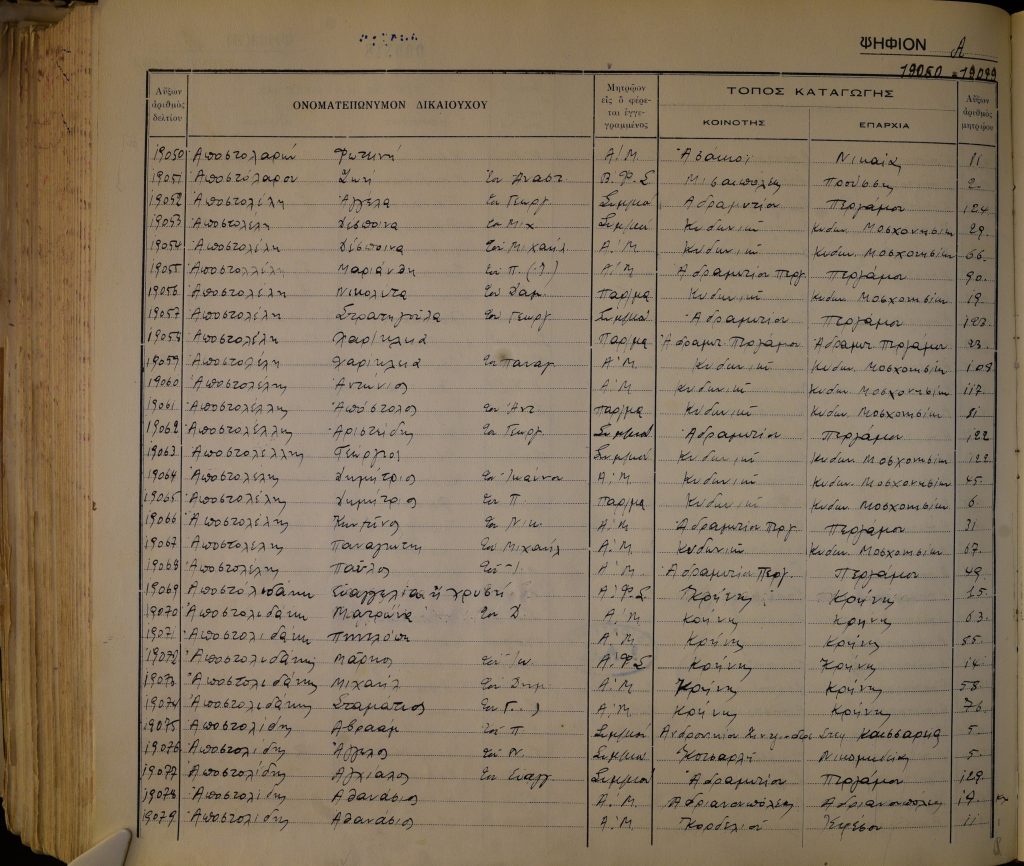

In 2021, Greek Ancestry and the General State Archives of Greece reached a collaborative agreement to digitize (through scanning and indexing) the Refugee Registers included in the Archives of the Evaluative Committees. These Registers, compiled in 1935, contain information about refugees who received compensation from the Greek State for the properties they had to leave behind in Eastern Thrace and Asia Minor. The collection consists of two sets of register volumes: urban and rural. There are a total of 25 register volumes, with 17 volumes for urban refugees and 8 volumes for rural refugees. Both sets of volumes are organized alphabetically by surname, for example, Vol. 3840 includes records of “urban refugees” with surnames starting with the letter “A,” while for “rural refugees,” the records for surnames starting with “A” can be found in Vol. 3832.

Each of the approximately 540,000 records in the Refugee Registers contains essential information such as the refugee’s surname, given name, the name of their father or husband, and the community and province of origin. In rare cases involving female refugees, the record may include the full names of both the father and the husband. Additionally, each record provides references to other refugee indexes, although limited information is available about these indexes, and it appears that not all of them are included in the Archives of the Evaluative Committees.

After indexing, Greek Ancestry also transliterated the records into Latin characters using its own formula. Consequently, both the original Greek version and the Latin-character version are now accessible on Greek Ancestry’s website. This allows users to search and access the records using either the Greek or Latin alphabet, depending on their preference.

It is important to note that despite the collection’s magnitude, it may not be exhaustive. The property compensation procedure was lengthy, and additional names might have been added before or after the compilation of these volumes. Two other factors should be considered: 1) the populations of Constantinople, Imvros, and Tenedos are not included in this collection as they were excluded from the Population Exchange, and 2) the refugee indexes only include those refugees who received compensation, that is people -mainly men- who had property in their name. Therefore, the dataset of 539,850 refugees does not cover the approximately 1.5 million people who migrated. Nonetheless, it remains a very representative sample that allows for drawing significant conclusions.

The Analysis

The completion of the digitization and indexing project coincided with the expressed interest of Greek-Canadian Data Scientist & Analyst, Joanna Koutsavlakis, to volunteer and collaborate with Greek Ancestry. Joanna and our team began working together to analyze the data from the refugee records collection. The initial task involved determining the exact map location of 966 places mentioned in the records. This task proved challenging not only due to the sheer number of places but also, and more significantly, because of name changes and the disappearance of many small settlements over time. Many of the villages that were once inhabited by Greeks until 1922-1923 no longer appear on modern maps. To overcome this, the team had to refer to historical maps from the 19th and early 20th centuries, testimonies of refugees, history books etc..

After the successful mapping of the 966 place coordinates in conjunction with the 539,850 refugee records by our team, Joanna created tables and maps that showcase the places of origin of the Greek refugees of Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace, along with the proportions between those classified as urban or rural refugees. These deliverables provide valuable visualizations of Greek presence in Asia Minor and offer a deeper understanding of the refugee population.

Note from Joanna: My name is Joanna Koutsavlakis, born in Toronto, Canada. Growing up, my parents emphasized the importance of my Greek heritage. Though my interest in Greek history and family stories was sparked after my grandparents had passed, I’ve been able to reconstruct our history through communication with other family members and personal research. Discovering this digitized archival collection, I contacted Gregory Kontos, who helped me find references to my 2x great-grandmother’s maiden name and confirmed our family’s residence in Voutzas, Smyrna. Working with the data of this collection has been invaluable! My hope is to continue this work, uncovering more priceless information from these records, so that the struggles and triumphs of our ancestors are not forgotten.

Geographical Origins of Greeks in Asia Minor

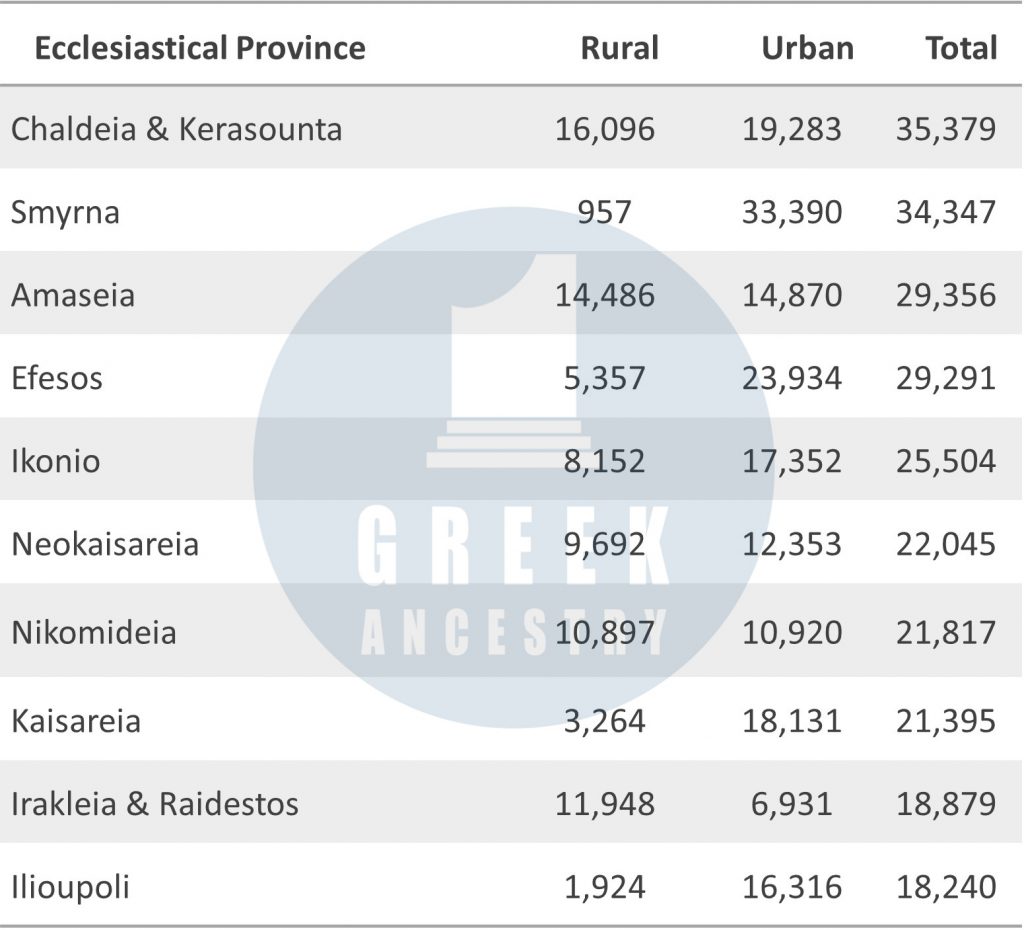

Table 1 shows the Top #10 Asia Minor provinces with Greek population, according to the data of the refugee records collection. The ecclesiastical provinces of Chaldeia & Kerasounta [spanning, more or less, from the area east of Ordu (Κοτύωρα) and west of Trabzon (Τραπεζούντα)] and Smyrna clearly dominate, including almost 70,000 refugees or abt. 13% of our sample. These two are followed by another pair of provinces with equal population, those of Amaseia [the area of Amasya (Αμάσεια), Samsun and Sinop (Σινώπη)] and Efesos [including the whole area from Kuşadası (Νέα Έφεσος) to Manisa (Μαγνησία) and Menemen (Μαινεμένη), excluding the areas of Krini, Smyrna and Vryoulla]. The fifth province on the list is that of Ikonio (Konya) in West-Central Asia Minor, followed by Neokaisareia [spanning from Ordu to Kastamonu (Κασταμονή) with the exception of the area of Amaseia], Nikomideia (İzmit) to the east of İstanbul (Κωνσταντινούπολη) and Bursa (Προύσα), and Kaisareia (Kayseri) in Central Asia Minor. The last two provinces in the Top #10 list are those of Irakleia & Raidestos in Eastern Thrace, west of İstanbul, and Ilioupoli [including Aydın (Αϊδίνιο) and spanning from Muğla (Μούγλα) to Ödemiş (Οδεμήσιο)].

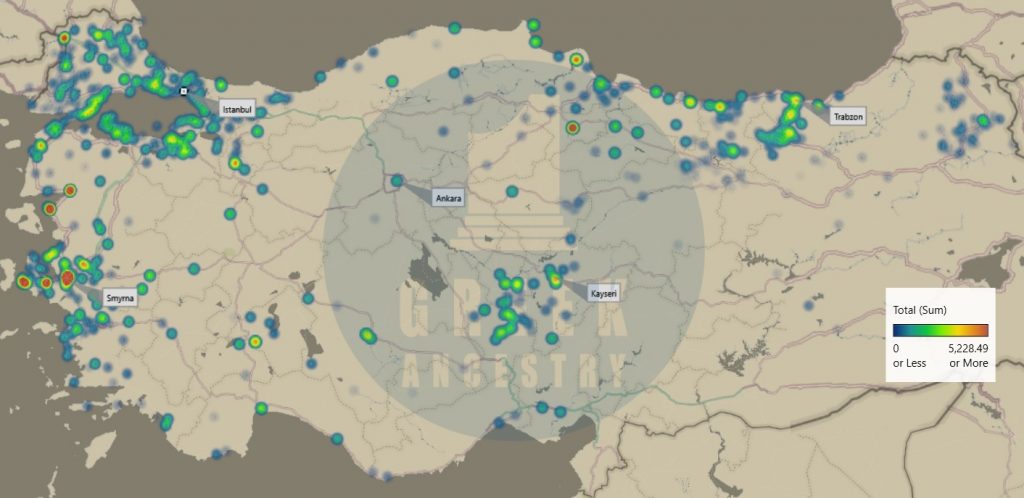

These findings can also be seen on Map 1, where all the provinces are represented. From the borders with Greece in Thrace and all the way to Armenia, Greeks could be found in almost any area of Asia Minor. However, concentration was greater on the coasts, where economic opportunities and accessibility were advantageous. But even as deep as Kayseri, concentration was far from negligible. Maps 2 & 3 offer a more clean perspective.

The areas of the map which seem to have big Greek populations, though not big enough to make it into the Top #10 province list, are better represented in the Top #20 list of the towns with the greatest Greek populations (Table 2). Of course, the population of Smyrna by far outnumbers that of other towns in the list. Nonetheless, some other towns are also interesting. We did not see the province of Kydonies & Moschonisia in the Top #10 provinces list, however, its capital, Kydonies (Gr. Κυδωνιές, aka Gr. Αϊβαλί, Turk. Ayvalık), comes second in this list with a total of 8,972 refugees. Similarly, we see Adramytio (Gr. Αδραμύτιο, Turk. Edremit), which is located a bit north of Kydonies, and Vryoulla (Gr. Βρύουλλα, aka Gr. Βουρλά, Turk. Urla), located between Smyrna and Alatsata (Gr. Αλάτσατα, Turk. Alaçatı). Of the other big towns whose provinces were less populous than the Top #10, we see Adrianoupoli (Gr. Αδριανούπολη, Turk. Edirne) in Eastern Thrace, Sparti (Gr. Σπάρτη, Turk. Isparta) north of Antalya (Αττάλεια), Alatsata and Krini (Gr. Κρήνη, aka Gr. Τσεσμέ, Turk. Çeşme) west of Smyrna, and Saranta Ekklisies (Gr. Σαράντα Εκκλησιές, Turk. Kırklareli) in Eastern Thrace.

All these were major urban centers, attracting domestic and foreign migrants seeking economic opportunities. However, in many cases, we should not underestimate the number of the indigenous Greek populations, who preserved their Christian faith and -though not always- their Greek language through centuries of Ottoman rule.

Rural & Urban Refugee Proportions

With the exception of the town of Pafra (Gr. Πάφρα/Μπάφρα, Turk. Bafra), in all the other cases in Table 2, those refugees who requested to come under the “urban compensation plan” by far outnumbered those who requested the “rural plan.” The example of Smyrna, where 24,519 refugees chose “urban” against only 290 who chose “rural,” is very characteristic. Apart from that, however, we see something similar happening in most of the Top #20 towns listed above. Of course, this is not surprising, as we are talking about urban centers. Nonetheless, it is in line with two realities: 1) the Greek population of Asia Minor generally lived in urban areas, 2) refugees generally preferred the “urban plan” hoping to receive some money in their pockets and smoothly settle in their new homeland. Map 4 below shows the great prevalence of “urban refugees,” especially on the populous coasts and in Central Turkey. Rural populations were found in the fertile lands of Eastern Thrace and the coast of Pontus.

Focusing in on the area of the west coast (Map 5) the predominance of urban populations is really impressive (Map 5). This is not irrelevant to the history of migration in that area. Encouraged by the more friendy economic, social and political environment after the Ottoman Reforms between 1839 and 1876 (known as Tanzimat), many Greeks settled from mainland Greece and the Aegean islands in the coastal towns of western Asia Minor.

These maps tell the end of the story of Hellenism in Asia Minor, however, they allow us to partly reconstruct that story. As our team continues to process the amazing data included in the refugee records collection, more interesting information and conclusions will come to light.

About the Authors

Gregory Kontos: Historian (PhDc.) & Founder of Greek Ancestry.

Joanna Koutsavlakis: B.Sc. in Geography and Urban Studies (McGill University, 2016); post-graduate certificate in Data Science and Analytics (Ryerson University).

About Copyright

All maps and tables presented in this article are the product of original research by Joanna Koutsavlakis and Greek Ancestry. Their use is allowed only upon written permission of both parties.