By Gregory Kontos

To dive into family history, you need to understand your sources. This has been quite often noted in Greek Ancestry articles and webinars, yet it has to be repeated until it becomes a sine qua non in our research. Why, when, how, where and by whom was a record created in the first place? What does a record tell and how can you verify its information? What information is missing from a record and what are your alternative sources to find he missing pieces? And most importantly, what can the story of a record tell about your own family history? This article will present a type of record which has never been systematically used in Greek genealogy research before, that is, parish voter lists.

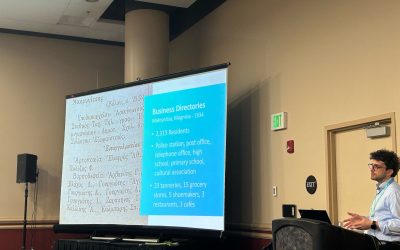

On August 1st, 2020, Greek Ancestry released a collection of 36,000 parish voter lists for about 100 villages of Lakonia. As hundreds of people rushed to the website and started searching for their family names, they all had this one basic question: what is a ‘parish voter list’ and what information does it include? A definition of a ‘parish voter list’ would read: a register of people eligible to vote in the elections of a parish’s new priest. Sounds interesting, doesn’t it?

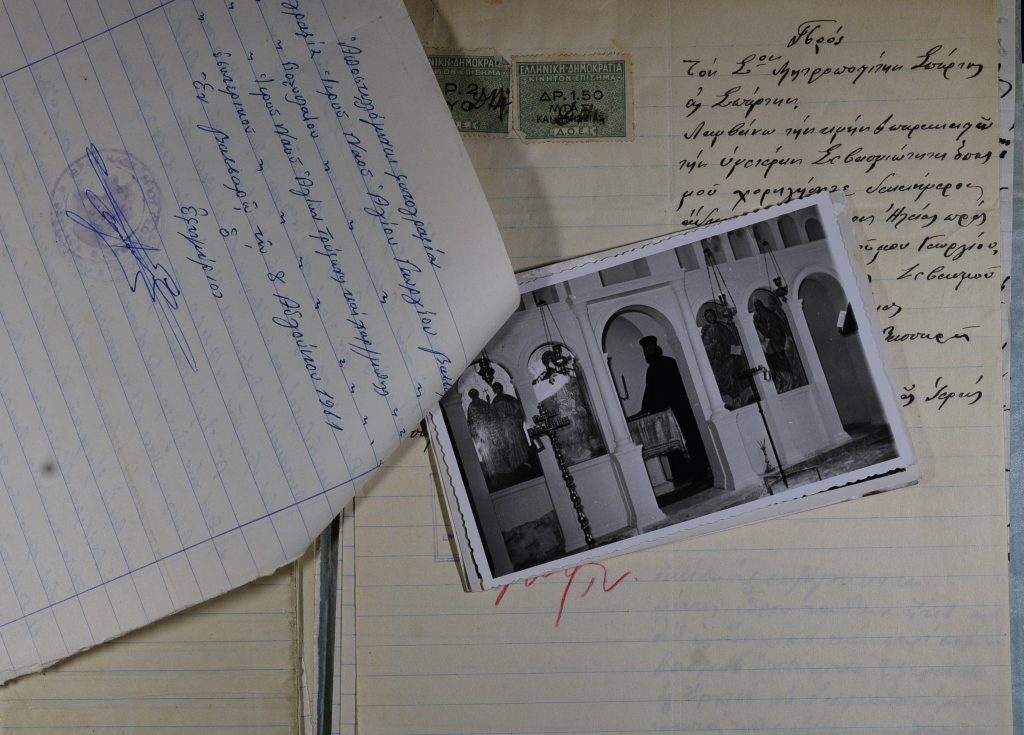

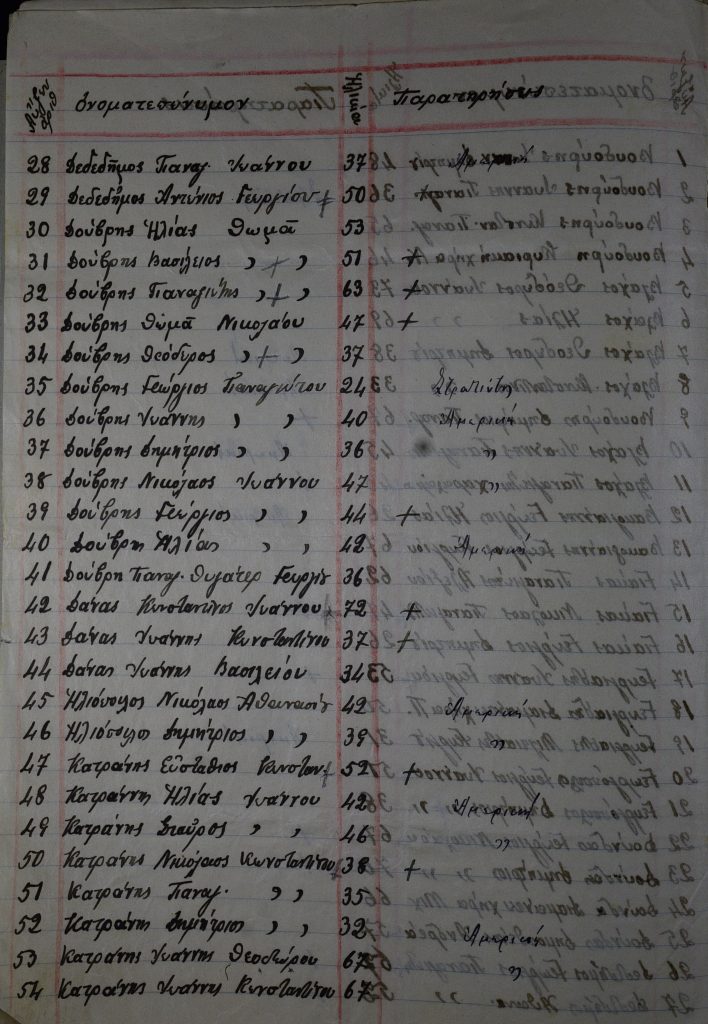

Today, priests in Greece are appointed and paid by the State, however, this has not always been the case. Until 1967, the situation was quite different: each parish would elect and compensate its own priest. Most villages would constitute one parish, while bigger villages and towns could correspond to more than one parish. Every time a priest would pass or move elsewhere, the parish was in need of a new priest, who, again, had to be voted for and paid. Every election required the composition of a register of all parishioners who were eligible to vote for the new priest; therefore, a voter list was created, mentioning, in most cases, the voters’ names, their age and and father’s name. The voters were the heads of households, in other words, married males, therefore we generally do not come across very young voters. Interestingly, the lists often include females, as well. That could happen when a household had lost its head, in which case the widow could take her late husband’s place as a voter. But in some cases we may also find older girls, who most likely had lost their father and were not yet married!

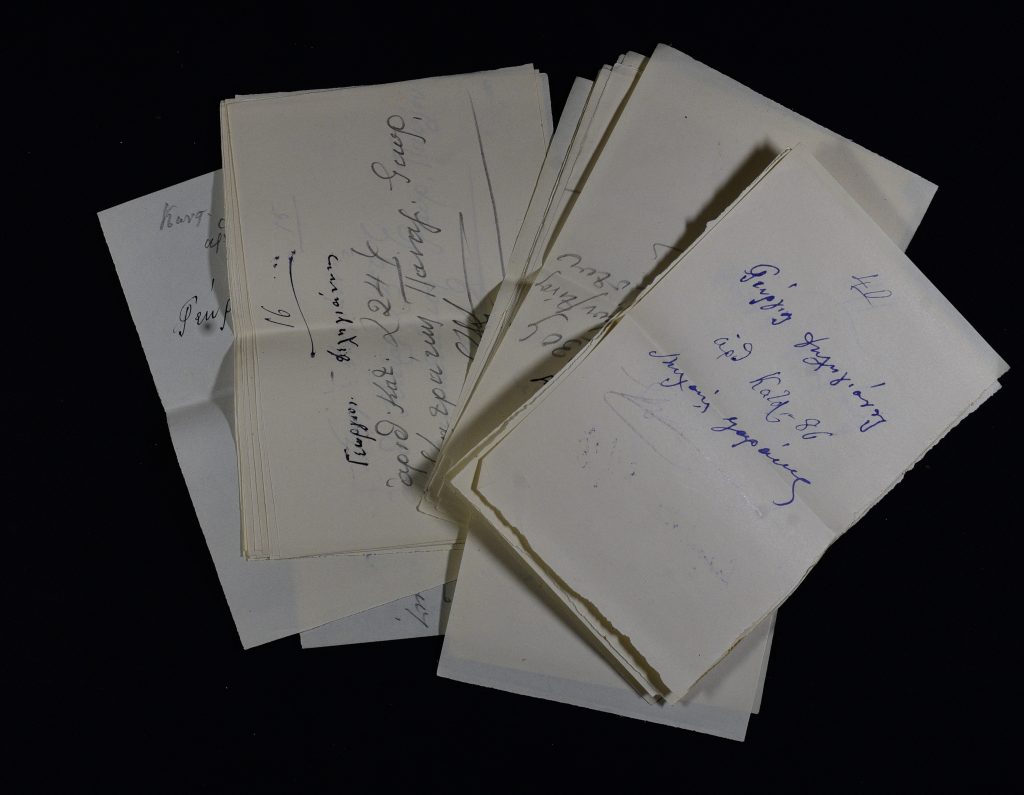

Meanwhile, the vacancy was announced, and candidate priests were recommended. In many cases, there was only one candidate. That was the case, for instance, in Voutianoi, Lakonia, in 1925, and the candidacy of Fr. Ioannis K. Tzannetos. On the contrary, in Dafni, in 1939, seven priests competed for the same one position. When candidate priests were located, the election date and time was announced to the parishioners and a notice was put on the local church’s front door. On the selected day, the church’s “kampanes” (bells) would ring and parishioners would gather to vote for their favorite candidate. They would write the name of their favorite on a small piece of paper. At the end, when voting was over, a committee would gather all the votes and start counting to see which priest came first. Finally, they would tie all the votes with a thin rope, put them in an envelope and send them to the local Bishop for approval, together with the election minutes and the voter list. The priest who had received the majority of the votes was then officially recognized and appointed by the Bishop.

That sure was pretty easy for Fr. Tzannetos in Voutianoi. As the only candidate, his election was not a surprise: he received 68 votes. But had he not been the only one and had there been some intriguing competition (which often was the case), this story could prove even more interesting for us today… On each one of those little papers one can not only see the name of the voted candidate, but also the voter list number of the voter. In this way, one could find out today which priest his ancestors voted for over a hundred years ago!

© Greek Ancestry

These having been said, every time we find one of our ancestors in a parish voter list, we can now imagine and reconstruct such a story. The history of the collection is part of our own family history.

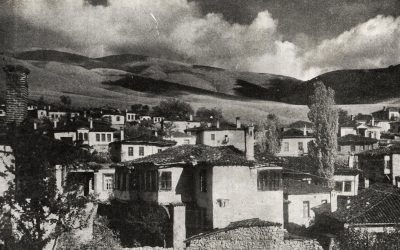

These parish voter lists are a valuable resource not only because of the magnitude of the collection, but also -and primarily- because of the time period it covers. The majority of these records were created between the 1910s and the 1930s, a time of big changes: emigration from Greece continued well into the 1910s; continuous wars drained the country from 1912 to 1922; Greek Orthodox refugee populations arrived from Asia Minor after the Catastrophe and settled all over the country; the 1930s were a period of relative peace, right before the outburst of WWII and the huge losses that brought. In other words, this collection is chronologically situated within a timeframe of big changes, and the information it includes may not be found elsewhere.

Future immigrants and the relatives of those who had left in the previous two decades, people who fought during the early wars of the century or those – soldiers and civilians – who fought, resisted or died during WWII, may all appear in records of this period. At the same time, however, it is paradoxical that despite their obvious relevance, these decades have been significantly underserved in Greek genealogy research, due to the lack of archival availability and accessibility issues.

It is for all these reasons that this new collection can prove so helpful for the Lakonian family historian. The fact that these records have been preserved deserves our applause, and the fact that Bishop Efstathios of Monemvasia and Sparta trusted their digitization and indexing to us is a true blessing for our field of Greek family history and genealogy research.

Learn more about this collection here!