The Greek state in the early 20th century has been hallmarked by political and ecclesiastical instability, economic strife, and war thus leading to mass emigration to the United States. Nationalism, ecclesiastical affinities, and culture traveled alongside Greek immigrants to the United States, leading them to turn inwards in the communities they established. Greek immigrant communities in the United States, centered around the Greek Orthodox Church, began mirroring the circumstances in Greece causing more instability in their communities and in larger American society. With the church at its focal point, Greek immigrant communities looked to church leaders for direction. However, with the arrival of Athenagoras I as the new Archbishop of America, his goals of centralizing the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America curbed rising tensions and instability in these communities, and allowing for Greek immigrants to retain their culture and patriotism while also assimilating into American society.

I. The Transition from Empire to Nationalist Projects

At the beginning of the 20th century the Balkan Peninsula underwent drastic changes as the Ottoman Empire continued to weaken over time and finally collapsed in 1922 after World War I. Nationalism led to newfound nations like Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria attempting to reconquer and repopulate previously controlled Ottoman lands. The imperialistic motives for reconquering these lands stemmed from a nationalist based historical claim. For example, Prime Minister of Greece, Eleftherios Veniezelos, reignited a movement based on the Μεγάλη Ιδέα (Great Idea), using it as a foundation for military campaigns eastward to the Western coast of Turkey.

Greek Royalists rejected the Venizelist project entirely. Followers of the Royalist (or Antivenizelist) faction stood by King Constantine XII’s neutral stance, thus tacitly aligning Greece with Germany during World War I. Royalist beliefs also advanced the King of Greece’s romanticization of Byzantinismwhile rejecting the idea of the assimilation of Greeks living in unincorporated territories still under Ottoman rule.[1]

These two opposing movements spearheaded by the most influential political leaders in early 20th century Greece trickled down to the Greek populace. This polarization took root in every aspect of Greek society. Greece remained divided between “Old Greece” and “New Greece,” and these regions became divided not only by historical, geographical, and cultural lines, but also by political lines.[2] These boundaries only exacerbated divisions amongst the populace of interwar Greece, as explained by George Mavrogordatos:

“Regionalism, and localism, including village patriotism, were, therefore, powerful forces in interwar politics. They manifested themselves even in the major urban centers, where groups organized by region or locality of origin (e.g., the Cretans in Athens) were essential in mobilizing political support and were thereby often entitled to representation on party tickets in both local and national elections.”[3]

This era in modern Greek history became famously known as the “National Schism,” and led to one of the modern state’s most insatiable periods because of this massive internal political turmoil. These regionalist politics extended beyond the Old and New Greek territories, but into national institutions such as the Greek Orthodox Church. Orthodoxy, as the state religion, functioned closely with the government.

Similar to King Constantine and Eleftherios Venizelos, who frequently alternated in and out of office, an identical dynamic existed within the Church of Greece and its metropolitans during this period. While serving as the head of the Church of Greece, Metropolitan Theoklitos aligned himself, as well as the Church of Greece, with King Constantine’s Royalist faction. On the other hand Metropolitan Meletios Metaxakis would align himself with Venizelos while serving as the head of the Church of Greece. This constant alternating led to dire consequences in the nation. The Church served as the focal point in Greek society. With political corruption and instability also affecting the second most influential institution in the country, many Greeks decided to immigrate to the United States in hopes of restarting their lives without corruption. Unfortunately, the National Schism and its effects would become a transnational intercommunal social crisis that traveled alongside Greek immigrants as they fled from war, and political and ecclesiastical instability.

II. A Transnational Crisis

Greek immigration to the United States dates back to the 1760s, with the founding of the colony of New Smyrna, Florida; however, Greek immigrants did not establish their first parish until the 1860s, with the inaugural Greek Orthodox parish established in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1864.[4] From then on, Greek Orthodox churches began sprouting up in the United States in all corners of the country. The establishment of these communities happened without oversight from the Ecumenical Patriarchate based in the Phanar District of Istanbul, Turkey. The early Church of America had to fend for itself partly due its distance from the rest of the Orthodox world.

With the National Schism dividing church leaders, political leaders, and civilians in Greece, it accompanied Greek immigrants to the United States thus exacerbating nationalist tensions. Due to the lack of understanding of American sociocultural norms and nativist attitudes towards immigrants, Greek immigrants in the 1900s faced xenophobic treatment from Anglo-Americans.[5] Anti-Greek sentiment permeated every part of the country where Greeks lived, escalating to the point of severe violence and ousting Greeks from their homes.[6] Society classified Greeks as part of the “new immigrant” class and perceived them as a threat to Anglo-Saxon White American society, similar to that of other ethnic groups coming from Southern and Eastern Europe.[7]It became imperative for the Greeks coming to the United States to retain their customs and ways of life to avoid feeling completely isolated from their mother country, especially under such dire conditions. These conditions only fostered the turning inwards of the Greeks in the United States; consequently, the diaspora only grew a greater fondness and pride for their country of origin. Communities of Greeks in the United States began to take the same shape as in Greece, divided along political and religious lines.[8] The polarized political atmosphere compelled many communities to split and form new churches. This pattern of churches dividing and splitting amongst each other took place across the United States, giving rise to one of the critical problems that the future head of the Greek Orthodox Church of America Athenagoras I would soon fix: pseudo-dioceses.

III. Archbishop Athenagoras and his Plans for Reorganization

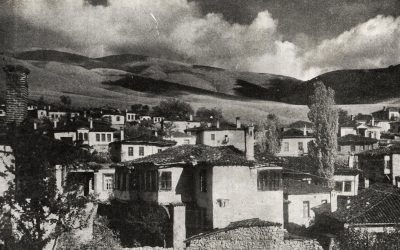

Archbishop Athenagoras’ given name was Aristokles Spyrou, and was born to the middle-class family of Dr. Matthew Spyrou and Helen Mokoros on March 25, 1886. Despite coming from the remote Aromanian village of Vasiliko, Athenagoras received an excellent education, attending high school in Ioannina before moving to Istanbul to study at the Theological School of Halki.[9]

Following Athenagoras’ education at Halki and ordination into the priesthood, Metropolitan Meletios Metaxakis of Athens ordained Athenagoras as an archdeacon, and appointed him as his secretary after serving the Metropolis of Pelagonia from 1910 to 1918. Under Metaxakis’ leadership, Athenagoras matured as hierarch, and excelled in navigating church politics. Kitroeff explains that Athenagoras “was less interested in abstract theological arguments than in the practical art of church governance. He was a protégé of Meletios.”[10] Metaxakis’ guidance in understanding the ecclesiastical world combined with living in a politically charged environment made Athenagoras the ideal leader for the budding American community distraught with political and religious sectarianism.[11] Athenegoras proved himself a politically adept asset who– even after Metaxakis’ removal from office in 1920 following the general election upset– kept his strategic position in the Church of Greece. In 1922, he was elected Metropolitan of Corfu and Paxi.[12]

While Athenagoras worked to rebuild the Metropolis of Corfu and Paxi, the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America deteriorated rapidly under the supervision of the current hierarch there, Metropolitan Alexander. After 1920, the ousting of Archbishop Metaxakis and the reinstatement of Theoklitos led to more upheaval both in the United States and in Greece.[13] The Holy Synod of Greece summoned Alexander multiple times. His refusal to appear before the Synod further escalated tensions between the Royalist-backed Holy Synod of Greece, the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and the communities in the United States. This incident led to Metaxakis and Alexander both being declared schismatics by the Synod. Metaxakis and Bishop Alexander countered this claim by the Holy Synod accusing its members as usurpers.[14] The Ecumenical Patriarchate then sent Metropolitan Damaskinos of Corinth, on a trip to the United States on May 20, 1930, to survey the state of the Greek communities for seeking out the most appropriate bishop to resolve this escalating matter. The Greek-American press and Alexander fiercely criticized this trip.[15]

During this trip, Alexander and the other metropolitans of the dioceses of San Francisco, Chicago, New York, and Boston, became agitated, sending out another round of encyclicals and letters, ultimately showing the level of fragmentation throughout the archdiocese. The majority of hierarchs turned on Alexander for his inability to oversee the archdiocese, and his frequent insubordination.[16] Meetings to discuss the next steps of the archdiocese on July 17, 1930, concluded with the deposing and stripping of Alexander’s full authority from the archdiocese on June 19, 1930.[17] Metropolitan Damaskinos’ motion to appoint the Metropolitan of Corfu to this position initially caused resistance because many perceived him as an outsider who lacked knowledge of the circumstances in America.

The ten years of instability in the Greek Orthodox communities of the United States began to transform into unity with the enthronement of Archbishop Athenagoras on February 26, 1931, in New York City at the Church of St. Eleftherios. His enthronement ushered in a new era for the Greek Orthodox Church in America– opportunity to forge stability for itself. For his first act as archbishop, Athenagoras made it a point to visit every Greek Orthodox community within the United States, surveying how each community ran itself.[18] Through conducting this large-scale study, Athenagoras gained a clear understanding of the issues facing this archdiocese and precisely identified their needs, including pastoral support, financial assistance, and general backing from a higher authority such as the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

Athengoras understood that the Greek immigrant communities needed a unifying and reliable system for their churches. He also took into account the need for more resources for the communities in major cities home to many Greeks, like Boston and Chicago.[19] For example, there were no Greek Orthodox seminaries and few religious schools in the United States before Athenagoras. Many priests who served there came from Greece. This presented two problems: first, the issue of political affiliation, and second, the need for more training and a deeper understanding of Orthodox canonical laws. As mentioned previously, laypeople began to serve as priests without the proper training and certification from the church, which consequently led to disorganization and violations of ecclesiastical law. This disorganization extended beyond laypeople impersonating priests and encompassed certified priests from Greece who lacked proper training.[20] These clergy also came to the United States with specific political affiliations because of the National Schism in Greece leading to multiple congregational splits.

At this point, the archdiocese had been “autocephalous,” or self-governed. A constitution created at the First Clergy-Laity Conference in 1921 formally recognized the archdiocese as an autocephalous institution by the United States and the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Bishop Alexander outlined the roles of the bishops in the following clergy-laity conference in August of 1922.[21] Much of the disorganization refers to Metaxakis’ involvement in establishing the archdiocese. This framework did not prosper, and Athenagoras recognized this in his speech by stating that a new constitution would repeal these regulations and solve this crisis.[22] After reporting the state of the archdiocese, Athenagoras clearly outlined what needed change and what this new constitution would enact. The main two most important changes that Athenagoras declared in his speech were as follows: 1) Bringing the archdiocese back into the fold of the Ecumenical Patriarchate; 2) the role of the priests and increasing support for them.

Firstly, having the archdiocese operate under the guidance of the Ecumenical Patriarchate gave the archdiocese much-needed structure and centralization. Athenagoras highlighted a significant consequence of not having the Ecumenical Patriarchate have jurisdiction over the Archdiocese of America, which created substantial administrative and financial issues with the dioceses in the United States: “Another consequence of the autonomy was the variety in the administration of the various bishoprics [dioceses] and on top of that there was a division of the small powers, which also led to the fact that the debt of the Archdiocese today amounts to many thousands of dollars and that the debt becomes a weakness.”[23] As a result of the National Schism, bishops in the United States essentially created their own dioceses. As Athenagoras previously explained, this resulted in large amounts of debt. At the time of Atheangoras’ arrival to the United States, the archdiocese could not balance its $30,000.00 budget and the creation of these pseudo-diocese only made it worse.[24] While operating under the direction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, Athenagoras also actively worked to reduce the archdiocese’s debt. One of his actions towards this effort included reducing his own salary and also lowering the salaries of priests.[25] In 1935, Athenagoras managed to balance the archdiocesan budget and create a small surplus of money.

The dioceses also contributed to the problem of multiple communities constantly fracturing. The creation of auxiliary bishops, the dissolving of the dioceses, and the Holy Synod solved this administrative issue. Auxiliary bishops had no diocesean or administrative rights.[26]The Holy Synod functioned as a group that oversees the appointment of bishops and ecclesiastical laws within the diocese. Following the dissolution of the Synodic System, Athenagoras appointed the auxiliary bishops who then carried out duties assigned by him. With the dioceses of Boston, Chicago, New York, and San Francisco no longer present, the archdiocese took full jurisdiction over every church in North and South America.[27] This new and centralized system in place made it easier for the archdiocese to streamline its efforts. Without so many different stratifications of power, Athenagoras ensured that at the higher levels of the church, disorganization would not take shape again.

Secondly, facilitating support for the priests played another significant role as it related to the improvement of the archdiocese. The church acted as the hub for the Greek immigrant communities, but the priest assumed responsibility for facilitating all the church’s services and ministries. With little to no unifying or centralized guidelines to follow, significant influence from the laypeople, and lack of financial support, priests around the United States struggled immensely to fulfill these duties. The priest assumed a role far more important than an ecclesiastical member– they emerged as essential figures deserving recognition and profound support for preserving Greek heritage and the Orthodox tradition in the United States. Athenagoras sought a transformative shift to elevate them from a position of insignificance to becoming key players in his overarching centralizing mission. Empowered priests not only served as points of importance for religious practices but also acted as community leaders prepared to guide Greek immigrant communities in their spiritual and cultural endeavors.

By equipping priests with the necessary resources, Athenagoras envisioned a clergy that transcended the limitations caused by scarcity, both in materials and education funds. To do so, Athenagoras arranged salaries for his priests to alleviate their personal financial struggles. In 1934, along with the Mixed Council, Athenagoras approved three levels of salaries based on their education. According to George Papaioannou, “The basic salary for those holding a degree from a theological school was $200.00 a month. For graduates of ecclesiastical schools or teachers academies, $175.00 a month, and those of only high school education, $150.00 monthly.”[28] Athenagoras held his priests in very high regard, and because the church remained the focal point of every Greek community in the United States, priests needed the recognition and financial support to keep the church in order for the sake of the community.

The National Schism in Greece ended, leading to an end as well to transnationalism and political fracturing in the United States. Even with the rise of dictator Ioannis Metaxas on August 4, 1936, clashes between Royalists and Venizelists did not occur as they had 20-25 years ago.[29] With the end of schism in Greece, communities finally started seeing progress in terms of political fracturing. Priests, on whom the schism had a significant impact, also improved. They began to take control over running the church and organizing services and other ministries while still coordinating with the parish councils, which now most members from community organizations became a part of. However, most priests still came from Greece, and with these immigrants and their children becoming more Americanized, the archdiocese needed a fully functioning seminary to preserve the Orthodox priestly traditions but still cater to the first generation Greek-Americans. Establishing a seminary would minimize the demand for priests from Greece, financially aiding the archdiocese. It also allowed these assimilating generations to connect more with their heritage. In 1937, Athenagoras established the Theological School of the Holy Cross in Pomfret, Connecticut, before it moved to its modern-day location in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1966.[30] The opening of this seminary significantly impacted the Greek community in the United States, saving the archdiocese financially and ensuring a reliable system for priests to feel fully equipped before moving to a parish to start their careers. It created a positive cycle within the Greek communities in the United States– communities began to blossom with dependable priests who knew the traditions, catered to the first generations of Greek-Americans, and kept order.

About the Author

Vasiliki Rousakis is a University of California, Berkeley Department of History alumni and prospective graduate student. Vasiliki is currently interning at Greek Ancestry, focusing on the publication of pieces related to the history of the Greek-American community.

[1]Richard Clogg, A Concise History of Greece. (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 85. An example of the many Byzantinist components of the Royalists was King Constantine’s homage to the last Palaeologan Byzantine emperor Constantine XI by being ceremonially crowned “Constantine XII.”

[2]George Th. Mavrogordatos, Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece, 1922-1936. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 273.

[3]George Th. Mavrogordatos, Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece, 1922-1936. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 274.

[4]Alexander Kitroeff, The Greek Orthodox Church in America: A Modern History (London: Northern Illinois University Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press, 2020), page 17.

[5]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 63. Saloutos in this excerpt explains that Anglo-Americans felt threatened by Greeks because they were “taking their jobs” away from them. This angered them even more because many Greeks did not have American citizenship.

[6]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 66-667. This quote refers to the Greektown riot of 1909 in South Omaha, Nebraska in which 1,200 fled the city because of the mob, including those of Austria-Hungarian and Turkish descent.

[7]Ioanna Laliotou, Transatlantic Subjects : Acts of Migration and Cultures of Transnationalism Between Greece and America. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 25.

[8]Saloutos, Theodore. The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 46.

[9]Demetrios Tsakonas, A Man Sent by God: The Life of Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople. (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1977), 8.

[10]Alexander Kitroeff, The Greek Orthodox Church in America: A Modern History. (London: Northern Illinois University Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press, 2020), 59.

[11]Alexander Kitroeff, The Greek Orthodox Church in America: A Modern History. (London: Northern Illinois University Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press, 2020), 60.

[12]Demetrios Tsakonas, A Man Sent by God: The Life of Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople. (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1977), 15.

[13]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 283-284.

[14]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 285.

[15]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 299-300.

[16]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 300-301.

[17]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 302.

[18]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 305.

[19]Alexander Kitroeff, The Greek Orthodox Church in America: A Modern History. (London: Northern Illinois University Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press, 2020), 60.

[20]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 129.

[21]Theodore Saloutos, The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 289.

[22]Spyrou Athenagoras, Fourth Clergy-Laity Speech, November 16, 1931. (From Greek Orthodox Archdiocese Archives, L02KY0001. Accessed November 28, 2023), 6.

[23]Spyrou Athenagoras, Fourth Clergy-Laity Speech, November 16, 1931. (From Greek Orthodox Archdiocese Archives, L02KY0001. Accessed November 28, 2023), 5.

[24]Papaioannou George, From Mars Hill to Manhattan: The Greek Orthodox in America Under Patriarch Athenagoras I. (Minneapolis: Light and Life Pub. Co., 1976), 92.

[25]George Papaioannou, From Mars Hill to Manhattan: The Greek Orthodox in America Under Patriarch Athenagoras I. (Minneapolis: Light and Life Pub. Co., 1976), 92.

[26]Demetrios Tsakonas, A Man Sent by God: The Life of Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople. (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1977), 26.

[27]George Papaioannou, From Mars Hill to Manhattan: The Greek Orthodox in America Under Patriarch Athenagoras I. (Minneapolis: Light and Life Pub. Co., 1976), 64.

[28]George, Papaioannou. From Mars Hill to Manhattan: The Greek Orthodox in America Under Patriarch Athenagoras I. (Minneapolis: Light and Life Pub. Co., 1976), 78-79.

[29]Theodore, Saloutos. The Greeks in the United States. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 332.

[30]Demetrios Tsakonas, A Man Sent by God: The Life of Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople. (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1977), 26-27