By George P. Zimmar

When they asked Socrates where he came from, he did not say ‘From Athens’, but ‘From the World’.

Michel de Montaigne

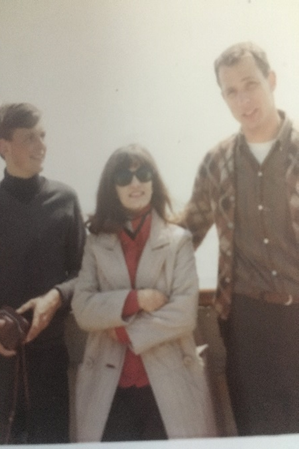

Early June mid-1960s: Colleges and universities disgorged their students, with some rushing to airports to catch charter flights for transport for a summer in Europe. The airports were crowded with duffle bags, back packs, Samsonite matched luggage sets, and the long-forgotten battered suitcase from the attic that Dad carried on his job search from city to city after the war. Most travelled with a friend or a couple of friends—girls with girls, boys with boys. Boy–girl travel would come later once the pill to prevent pregnancy had more adherents. Most youth were casually dressed with Levis or slacks with a shirt or top; but there were traditionalists in coat and tie and dresses or skirts topped with a sweater set.

There is no better person to travel through Europe with than my sister Peggy (Panayiota). A dedicated Europhile, in her teen years, Peggy had lived with our sophisticated Greek family, who spoke English, French and Italian, and she had absorbed the ways and ethos of Europe. After completing a bachelor’s degree in Education and teaching in Chicago schools for one year, she was now preparing to return to Greece to live.

Our plan was to take three weeks to visit major European cities that would include Hamburg, Brussels, Amsterdam, Paris, Geneva, Florence, Rome and push on to Brindisi for the crossing to Greece. That would give us a couple of days for each city and a day for driving in between. It would allow me about a month in Greece before my return home to the US. Peggy would stay in Greece.

We landed at Gatwick Airport outside of London and toured the venerable sites of the city. London was the likely destination to make a first exotic encounter with a foreign land, so the American Express kiosk was jammed with youthful travelers seeking the exchange of dollars for pounds. London was ablaze with youth culture. The Beatles’ rock band was on an ascending trajectory worldwide, denims were flared, shirts floral, and skirts mini, well above the knee. Hard drugs had not yet hit the youth scene, but marijuana travelled hidden in back packs. With little knowledge or care of who Lord Horatio Nelson was or what he accomplished, young people nonetheless crammed his square, at the feet of British lions surrounding his eminence. Our plan was to go to Goteborg, pick up a P122 Volvo two-door sedan and travel through Europe to Greece.

So, we boarded a ship to traverse the North Sea to our destination. It was midsummer, the old single-smoke stack ship was Swedish, and the summer solstice celebrations were underway throughout the longest day of the year and into the shortened night. Our fellow passengers were Swedish young people returning home, or English youth on their way to visit Sweden. Cool ocean breezes prevailed, and a good deal of drinking warmed body and soul. Peggy and I made friends with our fellow travelers, and we enjoyed being the only Americans on board.

The North Sea is treacherous any time of the year. On the afternoon of the second day, a fierce summer squall hit the ship, and waves covered the bow all the way up to the forecastle. Glasses and plates slid to the floor. One of our friends, somewhat inebriated, was swept by a wave across the bow deck to the ship’s rail, but was able to get up and stagger to safety. The rest of the trip was uneventful, and we arrived in Goteborg harbor, rested and eager to go to the Volvo factory to pick up the car.

Cars in Sweden have steering on the left, but the opposing driving lane is to the right. So traffic comes at you from the right and turning right involves crossing the opposite lane. Moreover, European cars are stick shift, involving a clutch pedal to shift gears, which can be tricky when on a slight incline with cars behind you honking as you slide backward. We made it to Malmö for the ferry to Copenhagen and the security of right lane driving through our remaining travels.

Over the course of our travels, we noted a distinct difference at that time in the cultures of the cities of Northern and Southern Europe. In Hamburg, a German port city, pedestrians at street corners took care to obey crossing signals; in Italy last minute dashes across the street took place. A young woman walking alone in Malmö or Copenhagen could stride in security, her serenity undisturbed; in Milan or Athens she would receive unwanted attention and perhaps catcalls from males loitering in the streets. Bus schedule arrivals and departure times were strictly observed in Hamburg and Amsterdam, less so in Milan and Rome. An orderly reception at the hotel desk in Goteborg where we had made reservations was efficiently dispatched; in Paris after waiting for the desk clerk to arrive, we were greeted with a changed room arrangement. While the character of the cities differed, all charmed us.

In Hamburg we encountered a Greek. Peggy and I were speaking Greek, discussing which tour to take, when a voice called, “Eiste Ellinas?” Our ανακριτής (interrogator) was a Greek seaman, Hector, from the island of Poros whose ship was unloading cut lumber at the dock. He shared his observations about life at sea and recommendations about places to visit in Hamburg.

Another characteristic of Europeans was the dress code, which tended to be more formal than in the US. For men, jacket or suit, shirt with tie was common, even in recreational settings. Women dressed differently when out of the home. A dress, or skirt and top, makeup, and jewelry were the order of the day. Eveningwear tended to be even more formal. How one dressed said something about who you were, where you were from, and many took stock of appearance. On a streetcar, Europeans typically looked at other passengers’ dress and accessories, and made a judgment of social class and status. One look at my shoes on a European street showed, “Ach, he is an American.” In the United States, the distinction in dress between the social classes was considerably less distinctive and an indefinite predictor of social status.

Even the Greek philosopher Aristotle took care of his garments and appearance according to Timotheus, the Athenian. Along with dressing well, he also wanted his hair to be fashionable and tidy. Aristotle enjoyed wearing rings and was conscientious of how he displayed them. He might have had a lisp, and his lifestyle was healthy enough to keep him fashionably slender. Such details add a glimmer of humanity to the man who we otherwise know only through his written thoughts.[1]

In Paris, we stood contemplating the statue of philosopher and bibliophile Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592). Our companion was Claudia, an American student studying at the Sorbonne. The women appear somewhat uncertain as to why they are standing before Montaigne. But there is a good reason: He is an outstanding exemplar of the intellectual life of the West. Michel Montaigne’s significance to our Western identity is that he channeled the great works of Greece and Rome to the Renaissance and to our times. He authored over 30 books, most still in print, on almost every topic, and his influence is embedded in the curricula of every university. Peppered throughout his essays are references to and commentaries on the works of Greek and Roman writers. His library in his towered estate east of Bordeaux contained 1000 volumes of philosophy, history, poetry, and religion, arranged on five tiers of shelves in a semicircle.

The Galleria dell ‘Academia was easily the highpoint of our visit to Florence. When Michelangelo was asked how he created the beautiful 17-foot-high statue of the Biblical David, he said, “I merely chipped away the excess marble and the figure was revealed.” And there it has stayed for centuries, right where it was created. Unlike the equally beautiful, but damaged, marble statues of Greece—for instance, the Charioteer in the Museum of Delphi—all of the David’s body parts were intact.

Often antiquarian statuary is damaged through the myriad of calamities that take place in its original setting. But more often when these items are stripped from the site of their origin, they are purposely or accidentally damaged. The case sometime made by those who have removed antiquity from its original site is that it was an act of preservation and, that transplanted, the work was made available for viewing by the wider world. Nonetheless, once the antiquity’s origin and ownership are determined, and the host government is willing and able to accept the item’s return, it should be returned. Otherwise, the holder holds stolen goods.

Do you like this “Yiayia & Me” article? Help us with the next one!

Contact us to share your story… or consider making a donation by clicking here, and make your yiayia proud!

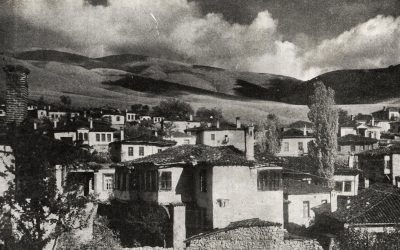

As we entered Patras harbor brilliant white-painted homes of the city greeted us; the air was brisk, the waves sparkled with silver, and the sky was a Magritte blue. Confusion prevailed as we disembarked. Moving an automobile off a Greek ferry is a chaotic affair, with passengers and vehicles nudging and pushing one another down the open gangway while other passengers and cars stand in a jumbled queue for a return trip to Brindisi. Adding to the din and bedlam on the docks were hawkers for guided tours, currency exchanges, taxis, and hotels. Such was our entry into Greece. It was an untidy scene, and I loved it. I was home.

Once in Athens, my sister and I were embraced by loving aunts, uncles, cousins, and various other family members. Everywhere we went in Europe, we enthused, we encountered Greece.

[1] C. Keith Hansley (2021), The Appearance of Aristotle. The Philosopher’s Hut.