By Sofia Pitsineli & Gregory Kontos

Greece in WWII

WWII broke out in Greece in October 1940, after the famous emphatic “OXI (NO)” that Greek Prime Minster, Ioannis Metaxas, replied to Italy’s request for free passage through the country and occupation of strategic points. After the Italian invaders’ rapid humiliation by the Greek Army, the time came for a joint attack by Germany and Bulgaria, in April 1941. Greece was defeated and divided into three occupied zones: Germany had Athens, Thessaloniki, the central and western part of Crete, some Aegean islands and part of Thrace. Bulgaria occupied the rest of Thrace and part of eastern Macedonia, while the rest of Greece came under Italian control.

With the royal family and government fleeing to Cairo and the appointment of a pro-Nazi puppet government, the Greeks decided to resist. In 1942, the first resistance groups were formed, most of them active in the mountains of Greece. Soon resistance expanded, and as successes became more and more worrisome to the Nazi occupiers, they decided to take effective action.

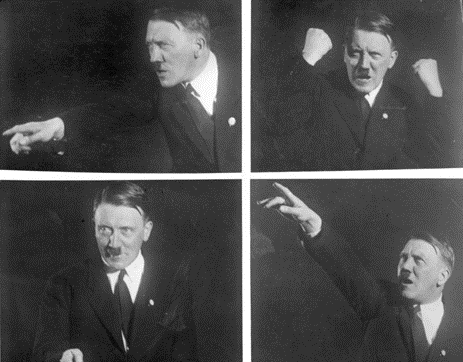

The Nazi Ideology

Based on the concept of the Aryan Race, the Nazi ideology encouraged the extermination of “inferior” races and groups: Jews, Slavs, communists, homosexuals etc. The same logic applied to anyone perceived as a threat to the Nazi regime, and while the Nazis perceived the Ancient Greek civilization as admirable and modern Greeks as a more or less “fine race”, the strengthening of the resistance soon led the Nazis to emphasize the “Balkan characteristics” of the Greek people. In their minds, the Balkan fighter was a savage, an anti-social person, a drop-out without any civil or military honor, equivalent to a common criminal. Therefore, getting rid of Balkan fighters and those who supported them was a necessity entailing no guilt.

The most cruel and horrible Nazi practice was retaliations. Retaliations were based on specific orders: if one German soldier was killed, one hundred Greek people should be executed. A shocking example of a group execution is that of May 1st, 1944. In April, a German general and three soldiers had been killed in Molaoi. In revenge, the Nazis killed random men in Molaoi and other towns nearby, one hundred people suspicious or arrested for resistance activity, as well as two hundred resistance prisoners in Athens executed in Kaisariani.

The executions were massive and impersonal. Usually, the Nazis did not even mention whom they were going to execute. Information was difficult to transfer and prisoner families did not know whether their loved ones had been executed or not. For instance, in the case of the May 1st, 1944, execution in Kaisariani, the names of the executionees were not officially announced, and the families of prisoners had to identify their people by searching for their clothes. A woman found the jacket of her older son, only to find the clothes of her younger son soon afterwards. Another woman found the jacket of her son; she fainted and a few days later she learned that her son had not been executed, but had lent his jacket to a friend of his in prison.

The “Second Office”

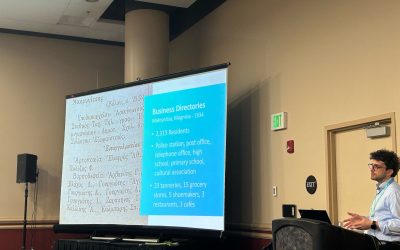

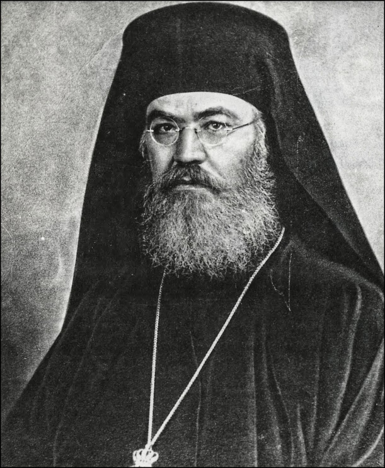

From situations like that arose the need for the collection of information. In April 1943, by order of Damaskinos, Archbishop of the Church of Greece, a special office, known as the “Second Office”, was established at the Archdiocese. Its official name was “Service for the protection of Orphaned Families”. Its main purpose was a) to collect information about the people who had been executed and inform their families, b) and to aid the families financially and morally, in order to help them meet their basic needs.

Director of the “Second Office” became Ioanna Tsatsou, sister of poet Georgios Seferis and wife of politician Konstantinos Tsatsos. Born in Smyrna in 1909, Ioanna had studied law and actively participated in the resistance against the Nazi occupation. Also, she took part in relief missions for the families of the executed, and helped British soldiers flee Greece.

With great efforts of the Archdiocese, the regional churches and Ioanna herself names of executed people started being collected, as well as information about their background, their arrest, imprisonment and execution. At the same time, the office started offering support to the families of the executed. At first, it was helping 45 families. By December 1943, their number had risen to 1854. In July 1944, at the end of the war, it was supporting 5923 families.

The “Second Office” managed to keep some of the information it had collected, despite the Germans’ relentless efforts to confiscate its records and end its operations. With the end of the war, the Office gave its records to the corresponding Ministry. However, during the events of December 1944, some of the records were destroyed. In 1945-1946, during the Nuremberg Trial, Ioanna Tsatsou offered information to the Greek representatives on behalf of the “Second Office”. This gave her the idea to actually publish the surviving information of the. She compiled a list and recorded the stories of the executed. Her book “Executed during the Occupation” was published in 1947, with the permission of the Archdiocese. The list, however, is not exhaustive. It includes about 800 names, while, according to Ioanna, about 20,000 Greeks had been executed during the Occupation.

Stories of the Fighters

Ilias Kanaris

Ilias Kanaris was born in Smyrna in 1911, and lived in Athens, on 14 Theotoki Str.. He worked as an engineer. After the German invasion, Kanaris, together with friends, organized a departure service for Egypt, transferring Greek and British officers, soldiers and individuals. In April 1941, Kanaris was arrested by the Germans and imprisoned.

During interrogations, he was forced to take the officers to the location from where the boats departured for Egypt. Accompanied by 7 Gestapo policemen, he went to the village of Vathy, Euboea, and showed them his friend’s house where a transmitter was hidden. When they arrived, he told the Germans to stay outside and let him in together with only one officer. As soon as he entered the house with the officer, he and his friend disarmed the officer and escaped from the back door. He was hiding for 7 months in Chalkida and when he was eventually caught, he was arrested and sentenced to death for attempted murder, illegal possession of a weapon and a transmitter, and for his escape.

While in prison, Ilias wrote letters to his family. Before his execution, he gave these letters to the priest who visited him in prison for a last confession. The priest then gave the letters to Ilias’ family. Here are two of his letters.

The first one was written to his brother: “My brother, I am the most severely judged of all. No convict has been sentenced to death three times. I have broken every record, and now that I am writing to you I am laughing. I want you to invite all your friends for dinner and read my letter to them. I do not want anyone to cry. I want you to behave like men and like Greeks. I am dying for my homeland (patrida) and you should do your duty and take revenge for all those Greeks who suffered the same. That’s what I want. Raise your glasses. Long live Greece. Long live the allies!”

The second letter was written to his son: “My dear child, Costa. When you read these lines, my child, I will not be in life. I will have been executed by the Germans. My child, my little boy, I am leaving you orphan, two years old. I want to tell you that I loved you very much, that I did not have the luck to make you happy and to play with you. When you are a man and you read the letter you will remember your father and the advice that I will give to you my beloved child. I want you to love your godfather more than me because he took care of you. Listen and respect him as a father. Love your mother and your aunts. My son, never play cards and do not offend any woman; be honest, sincere and a friend of the truth. Love your homeland and be a good Christian. Costa, my child, I’m leaving you in good hands; they will love you and take care of you. I want you to forgive me for leaving you an orphan. My little boy, I will die with your name on my lips and shout “Long live Greece” (Zito I Ellas). I kiss you sweetly my little man. Your father, Ilias Kanaris.”

Ilias was executed on February 24th, 1943. He was 32 years old.

Dionysios Gonatas

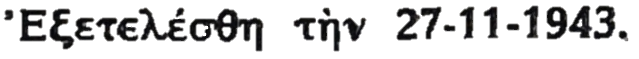

Dionysios Gonatas lived on 40 Liakataion Street, in Athens. He was from Kefalonia and worked as a lawyer. He had 80% percent disability, with both of his legs amputated. He was the president of the Association of Disabled People. He was arrested by the Germans, when they expelled the disabled from the hospitals and there was a demonstration against the forced conscription. He was executed on November 27th, 1943. He left a father and a younger sister with tuberculosis. During his execution, the Germans removed his wooded legs, threw him to the ground and shot him.

Konstantinos Bouras

The Archdiocese asked Father Konstantinos Grigoropoulos to visit the Averof prison in the evening of Friday, June 18th, 1943, together with three more priests. They had been requested by the Germans to come and confess the prisoners who were going to be executed on the next day. The Germans had not informed the Archdiocese about the number of prisoners to be executed. However, as 4 priests had been requested, the Archdiocese assumed that about 16 people were to be killed. The priests spent the night in the prison. Around 5am, they were taken to the prisoners. The time available and the whole setting were not fit for a confession. In every cell, the priest was accompanied by a German officer and a translator. Father Konstantinos wanted not only to let the prisoners confess before their death, but also to collect information about them, their families and the reasons why they had been imprisoned. Discreetly, he was keeping some notes. The last prisoner that he visited that day was Konstantinos Bouras of Meligalas, Messinia, a lawyer and former police officer living in Athens. Bouras had a lot of confidential information to give to the priest, but it was not safe to do so. So, the priest had an idea. When the prisoners were put in the little truck that would take them to the place of the execution, he joined them in the truck. The Germans officers accompanying them did not speak Greek. Many of the prisoners, including Bouras, started talking to Father Konstantinos, and he was keeping notes. They told him about their resistance activity, and about their families. A priest in a truck full of people about to be executed, trying to preserve their stories, trying to give them courage, promising that the Archdiocese would take care of their families. At some point, they started singing all together. When they arrived to the place of the execution, the priest followed them. He wrote: “That was the most difficult moment in my whole life. I was trying to hold back my tears, and with my teeth tightened I was trying to give courage to my children, until their last moments”.

Father Konstantinos recorded the last words of the fighters and their actions as warriors as they were being transferred to the death squad. He stood by their side till the end.

*This paper was presented by Sofia Pitsineli in the 2nd International Greek Ancestry Conference (Jan. 29th-30th, 2022). All the conference sessions have been recorded and can be watched on Greek Ancestry’s YouTube channel. Tsatsou’s book has been digitized by Greek Ancestry and the name list of the executed fighters has been included in Greek Ancestry’s searchable database.