By George Zimmar

Memory is the diary that we all carry about with us

Oscar Wilde

A visit to my Uncle Tom Zoumaras’s store involved a series of transit switches from the southeast side of Chicago to the northwest section of the city. We would walk from Drexel Boulevard’s all-white middle-class apartments, board a westbound streetcar at 47th and Cottage Grove Avenue—the border between black and white residences and the route of the annual Bud Billiken Parade[1]—and ride through the red-lined black business section. Army and Lou’s Rib Emporium, Casper’s Fresh Greens market, Sid Hersh’s Cleaners, Horowitz Meats and a myriad of other stores dotted 47th Street on the way to the El that sliced through the city. From there, the elevated cut through Chicago’s southside slums, factories, warehouses, and vacant lots and traveled roughly 55 city blocks north to the Grand Avenue exit, which was not far from the stately Water Works Tower built after Chicago was devastated by fire in 1871. A CTA bus then carried us west through largely residential areas to the Montclair Theater, owned by my Uncle Tom. My dad and his brother worked in an ice cream parlor next to the theater. The border of Chicago and suburbs was nearby to the west.

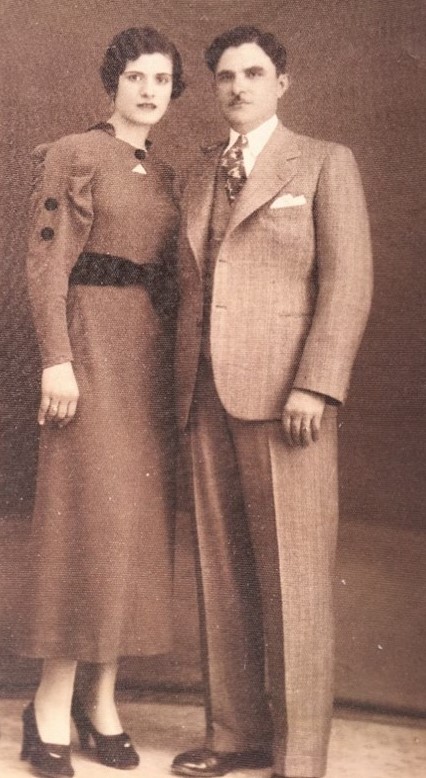

There is not much of a family record at the time of my birth, nine months after my parents married. The honeymooners, Peter and Sophia, returned to the United States from Greece to find that dad’s business had been mismanaged by his sister Stella (Styliani) and brother-in-law Louie to the point of bankruptcy. Perhaps it was improvident for Peter to have left his business with his sister and her husband, who had a gambling problem. But he had spent his life sending money to his parents and caring for his sister; now, nearing age 50, it was time for him to marry. So, he spent over a year in Greece until he met and married my mother in the spring of 1937 and came home with her to a ruined business. As a result, he went to work for his younger brother Tom (Athanasios), and we moved into an apartment near his store.

My very earliest recollection was to see my dad behind bars in a lock-up. Our apartment on New England Avenue was in a well-appointed brick building (after the Great Fire all housing in Chicago was brick) of about 12 apartments on a tree-lined street. The neighbors in the apartment below were elderly and tiresome and often complained that the foreigner’s kids, I and my younger brother, David, disturbed their tranquility. Moreover, as my parents walked from one room to another, I am told the neighbors would strike their ceiling with a broom in protest over the footsteps. We walked shoeless in the apartment, but the complaints continued until the neighbors filed a disorderly conduct complaint with the local judiciary for eviction. Dad came home late one evening to find a police car at the apartment door to take him to the lock-up. Next morning my mom brought us to the police station, where I saw my dad behind bars waiting to go to court. The judge took one look at the situation—my immigrant parents with small children in a crammed apartment and the elderly, irritable complainants—then angrily dismissed the case and chastised the police for the arrest. Soon after, as I was going down the back steps to play in the yard, the lady neighbor opened her door and, perhaps to make amends, held up a cookie as a peace offering, which I took. She said, “What do you say?” My response: “Can I have another one?’ The door slammed.

We were a family of four and my brother David and I rarely separated, ever embracing each other and playing together. Perhaps I was holding him to me rather than the other way around. My mother’s pregnancy with the third child, discussion was muted. Parents at that time did not discuss family matters especially if these were broadly related to sexuality. Today parents make an effort to discuss the new baby to be born with their children in preparation of the birth. As my mom was coming due with the birth of our sister, Peggy, arrangements were made to have David stay with my mom’s sister Angelike in Valparaiso, Indiana, and I was to stay with her cousin Uncle Tom Metos in Chicago. Nothing was said about these temporary living arrangements. Dad, David and I boarded the South Shore train and headed to Indiana, passing through the sooty Gary steel mills and the pastoral farmland beyond to my aunt and uncle’s roadside café, gas station, and farm at the intersection of US Route 6 and 49.

Do you like this “Yiayia & Me” story? Help us with the next one!

Share your story or consider a donation and make your Yiayia proud!

After lunch, my brother and I were next door at the Standard Oil gas station, fascinated with the working garage and the scores of dead flies frozen on the sticky fly paper strips hanging in the window, when dad came in and said, “We are going home. We have a ride to Chicago with the coffee vendor.” I was loaded in back of the panel truck bearing the aroma of coffee bags, and the truck left… without my brother. Looking out the rear window, I saw David receding by the roadside. I cried out that I wanted my brother back and broke into tears. Through the waves of bawling, my dad made an effort to tell me that the separation was temporary, only until the birth of the baby, but to no avail. I sobbed the 35 miles to Chicago. Later, in 1978, David was killed in a car accident not far from the road on which we traveled home to Chicago that day. I made the arrangements for the funeral and the mourning afterward without tears. Perhaps it was prescient that I had cried my heart out on losing him as the panel truck carried me and my dad away.

Just as World War II was ending, we moved from the northwest to the South Side of the city to 47th and Drexel Avenue. The railroad apartment came with a parlor, kitchen, dining room, three bedrooms, and a bathroom with a tub—all lined up along a hallway that traversed the apartment. One of the bedrooms came with a Greek tenant, Mike, who was the employee of the former residents, my mother’s cousins. Mike would go to the bathroom early in the morning with a towel draped over his pear-shaped body, shave, then go to his room, dress, and leave for the day. He would return late at night and go quietly to bed. On Friday he left his rent, $10, on the lamp table next to his room.

Our new residence was in a large corner apartment building that consisted of about 50 three-bedroom apartments with a large back yard. Each apartment had a 10’ x10’ back porch and a storage area in the basement where the laundry was done. On warm days, women would hang the wash out to dry on clotheslines strung in the yard. As the city became sootier from car exhaust and the steel mills to the south, the clotheslines were abandoned and the yard given over to the children in the building for play.

The ethnicity was broad, Irish, Italian, Jewish, German. My classmate, Helena Bloch and her family were in Munich during the war, and Eugene Dinkins’s grandparents came to the US just prior to the onset of war. Sy and Alan Hersh’s dad owned the cleaners on 47th street. The superintendent, who took pride in caring for the building, was German and my downstairs buddy, Shelly Gittleman, would converse in Yiddish to Horst who would reply in German. My memory of the place, as a six-year-old, just after we had just moved in on a brisk January day, with snowflakes swirling in circles, and wondering what living in our new home would bring.

[1] Largest African American Parade in the United States established in 1929.