By Giannis Michalakakos

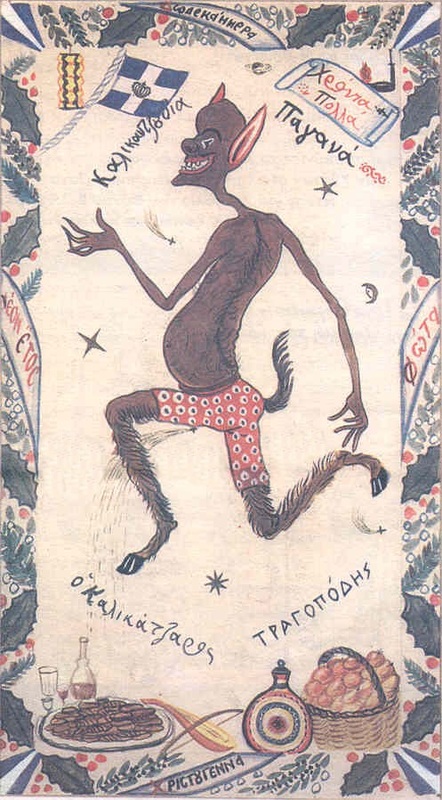

The tradition of Mani is rich of stories and poems referring to mythical and supernatural creatures. Many of them concern the goblins known by various names in the region of Mani such as “Kalikantzari”, “Likokantzari”, “Tsilikrota”, “Parorites (Arorites).”

They are little, black creatures in the size of a mouse! They have antlers, hairy legs and goat tails. They are particularly playful and naughty. Their description refers to the Satyrs or the Greek God Pan, and probably there is a connection between the various myths. They are not capable of doing great harm to humans, but they enjoy mischief and causing trouble…

According to tradition, from Christmas Eve until Epiphany (January 6th), they come out of the holes in which they hide and sleep, in order to tease humans, especially children and the elderly, and to mess things up.

In the region of Androuvitsa (Western Mani) they are called “Tsilikrota”. This name comes from the word “tseliki” or “tsiliki” (steel). People gave this name either wanting to describe the robustness of these creatures, or wanting to picture the color of their skin, which resembles the color of the steel.

The goblins called “Arorites” (“Paraorites”) are these who come out at night and hunt those people who go around after “normal hours”. That’s where their name comes from (paraorites i.e. those related to “after normal” hours). Holy water is their greatest fear. That’s why on the day of the Epiphany, when “waters are sanctified”, they disappear from the upper world.

On Christmas Eve at sunrise, the women of Mani gather and start making the traditional fried dough strips, called “lalagia”. Women meet early in the morning because at that time goblins are asleep. Sometimes though, goblins smell the frying oil, wake up and run towards the village. They scatter through the streets of the village, and wherever they smell the burning oil or see smoke coming out of chimneys, they quietly climb on the roofs. Then, they see the fried doughs “dancing” in the oil and they crave them. However, since they cannot reach them from the roof, they all pee into the pan because of their irritation. At that time, the oil starts to frizzle and spill and the fire goes out. The goblins disappear… The ashes in which the goblins have peed are not used by women in the laundry. They take and scatter them in the fields to repel the rest of the spirits and demons that wander until Epiphany. According to tradition, the house in which the goblins have peed, will suffer the whole year from bad luck.

During this twelve-day period, women and children go out and collect heaths, chamomiles and herbs. When they arrive home, they will scatter the chamomiles around every corner of the house and on top of the oven. They will use the herbs to plug up every hole in the house, even the keyhole, so the goblins cannot get in. They will burn the heaths and then “cense” the whole house, in order to exorcize the cursed “Tsilikrota”. Before leaving the house, the old ladies make sure to cover the holes of their shoes to be safe!

This article was originally published in Greek on Giannis Michalakakos’s Maniatika blog and has been translated by Greek Ancestry’s team. Michalakakos is a beneficiary of Greek Ancestry’s Village History Projects Initiative Grant!

Here is a well-known Maniot song about goblins that is sung until today: “We are goblins, we are out and about after normal hours, we want the lalagia, we take the children, give us the rooster or the hen, or we’ll break the door.” [“Αρορίτες είμαστε, αραρά γυρεύουμε, τηγανίδες θέλομε, τα παιδιά τα παίρνουμε, ή το (γ)κούρο ή τη (γ)κότα, ή θα σπάσαμε τη (μ)πόρτα.”]

Sources

Nikolaos Politis, “Meletai peri tou viou kai tis glossis tou ellinikou laou: Paradoseis – Part B”

Kiriakos Kassis, “Laographia tis Mesa Manis, Vol. B”

Kostas Pasagiannis, “Ta prota paramithia”