By Maro Rempoutsika & Gregory Kontos

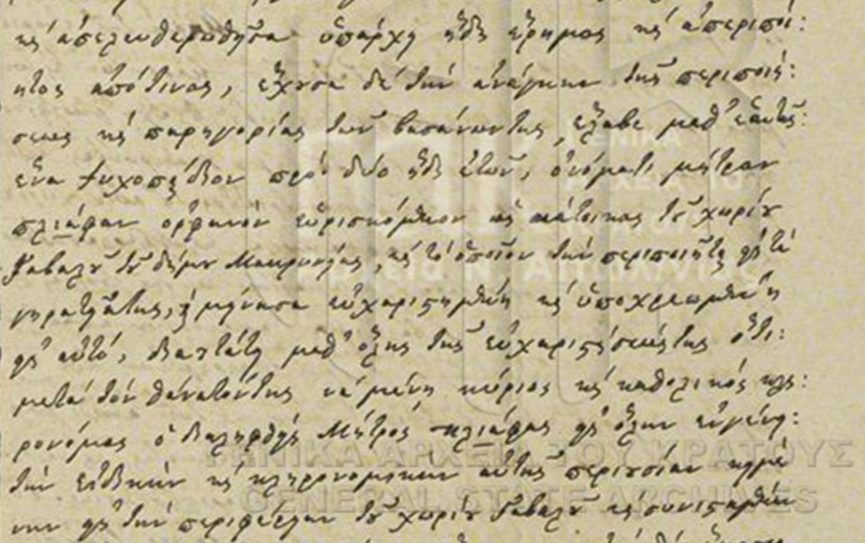

In a notarial record signed on the island of Kythera in 1564, back when the island was under Venetian rule, we learn about the details of an adoption contract.[1] In particular, a man named Georgis Maneas, agreed to accept a boy called Nikolas Koiriakois, son of the widowed Bella Sotirchous, as his “soul – child.” On her part, the mother agreed to grant to the adoptive father the boy’s share of his biological father’s property. At the same time, Georgis took Nikolas as his own child together with the obligation to cultivate his inherited field until the latter became an adult. When that happened, he promised to leave the child a share of his own property as well. The adoptive father undertook all the commonly known parental duties, such as the guardianship, clothing, nutrition, and guidance of his son. Lastly, it was stated in the contract that in case Georgis or Bella violated the agreement, either by not taking care of the child or by trying to take it back, respectively, there would be penalties.

This notarial document introduces us to the relatively unknown term of “soul – children” (ψυχοπαίδια) and to the requirements of the corresponding institution. But when did this term appear in the Hellenic world and what exactly was this special form of adoption?

The term “soul – child” describes an institution already existing in Byzantine customary law.[2] According to this, the “soul – son” or the “soul – daughter” are granted to the “soul – parent”, who in exchange for the child’s labor undertakes the obligation to ensure his professional development or endow her until she reaches the age of marriage.[3] In comparison to an ordinary adoption, the tradition of the “soul – children” was accompanied by a less formal legal relationship, and by a strong ethical character, which is also reflected by the first part [“ψυχή” (soul)] of this Greek compound word [“ψυχή” + “παιδί” (soul + child)]: this signifies the moral and religious attitude of the father, who aims not only at his inner atonement but also at the devotion of the adopted child to him during the last years of his life.[4] The benefits from the offered labor usually were not important.[5]

In general, information about “soul – children” can be found in very specific types of records, such as judgments, wills, dowry contracts and other notarial records, where the ethical character of the adoption, the responsibilities of the adoptive parent in terms of custody, endowment etc., the obligations of the biological parent but also the commitments of the adoptee are specified.[6] The limited number of available sources may be due to the customary nature of the institution, however, formalities varied depending on each case and the time period.[7] In Byzantine society, where the association of family was of great importance, adoptive kinship ties in general had become widespread and gradually more and more institutionalized, especially after the regulations of Emperor Leo VI.[8] Namely, law XXIV abolished the, until then, casualness of the adoption which allowed marriages between natural and adoptive children of the same father, since until then ecclesiastical ceremonies were not part of the procedure.[9] From then on, adoption was more officially established and was accompanied by religious solemnity and marital prohibitions. In fact, the adoption was validated during a ceremony at church, and then a contract secured the obligations and rights on both sides.[10] Moreover, law XXVII permitted to all women, such as sterile ones or eunuchs, to adopt for any reason, legitimizing in this way adoption, not as an act of patriarchy or power but as one aiming at the creation of a family tie.[11]

In this context, where the formality of the adoption as an institution was rather flexible, the adoptive children’s benefits and the parental commitments varied as well, and this was interrelated with the reason behind each adoption.[12] For instance, for a childless couple that wanted to ensure the continuation of the family line, the adoptive child would become their only heir.[13] In other cases, adoption came neither with the right to inherit nor with belonging completely to the adoptive family.[14] Other adoptions had a strong philanthropic character, like the institution of the “soul – children”, and focused on the upbringing and endowment of the child, but not necessarily with the involvement of inheritance issues.[15]

In the post – Byzantine era and during the Ottoman rule, the situation was once again different. As it is evident in legal sources of the 18th century, the traditional form of adoption had become rare, and alternative adoption practices, such as that of the “soul – children” became more popular. [16] It is argued by certain historians, who have contributed to the topic, that typically “soul – children” were not equated with the officially adopted or natural children of a family and consequently neither did they have the right to inherit, nor were marital limitations in effect for them.[17] Nevertheless, notarial documents are indicative of the uniqueness of each adoption case. A will of 1839, composed in Mesolongi, unravels the story of a widowed woman called Maria, living in Gavalou, Aitoloakarnania: after being widowed and losing her children who were imprisoned or probably killed during the heroic Exodus of Mesolongi, one of the most important historical events of the Greek War of Independence, Maria was left alone. Having the need for someone to console her and soothe her pain, she adopted a two-year-old orphan boy, named Mitros Pliofas, as her “soul – son”.[18] In her will, she designated Mitros as her full heir, provided that, in case any of her biological children shows up, then they will take a share of the property as well. Perhaps this is one of the possibly many similar cases of parents making no discriminations between their children, natural, or spiritual.

Discriminations, however, were not restricted to inheritance issues, which again shows the uniqueness of each case. The photograph above was taken in Geraki, Lakonia, around 1915. The family which was photographed was one of the village’s most prominent at that time, owning extensive olive groves, an olive press, the village’s café, a mansion and being related to the village’s religious leader, the priest. With a quick look, there is nothing striking, but with a little bit of family history context and a closer look, one detail can be detected. Five children are shown in this photograph, but just four were biological children of the parents who are seated center and left. The older girl, Konstantina, standing on the left of the photograph was in fact a “soul-daughter.” She was the lady’s 1st cousin, but coming from a poor branch of the family and being younger than the lady, she was taken in as a “soul-daughter,” helping with housework etc. Nothing indicates any sort of discrimination, but one single detail: her socks! While the family’s four biological children wore fine (and most of them matching) socks for the occasion, the “ψυχοκόρη” wore way simpler. Her total black socks did not resemble the fancy ones of the rest of the children. Although this detail can go unnoticed, yet it does indicate the “soul-daughter’s” different status in the family.

To conclude, the institution of the “soul – children” seems to have been continuing and evolving through the centuries, sometimes in an official and sometimes in a more unofficial manner, affecting in this way all the requirements of this distinctive form of adoption. We hope that this phenomenon with its unique sociological and historical interest and its continuity through time will attract more academic interest in the future, as so far it has been rather neglected.

Did you like this “Yiayia & Me” story? Help us with the next one!

Share your story or consider a donation and make your Yiayia proud!

[1] Emmanuel G. Drakakis, Emmanuel Kassimatis, Notary of Kythira (1560 – 1582), Athens: 1999, 160-161.

[2] P. I. Zepos, “Psicharion, Psichica, Psichopedi,” Bulletin of the Christian Archaeological Society, vol. 10 (1981): 22 (in Greek)

[4] Zepos, “Psicharion”, 22-23.

[5] Zepos, “Psicharion”, 23.

[6] Zepos, “Psicharion”, 23.

[7] Zepos, “Psicharion”, 23.

[8] R.G. Macrides, “Kinship by Arrangement: The Case of Adoption”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, vol. 44 (1990): 109-110.

[9] S.P. Scott, The Civil Law, XXIV, Cincinnati: 1932.

[10] Macrides, “Kinship by Arrangement”, 112.

[11] Macrides, “Kinship by Arrangement”, 111; Scott, The Civil Law, XXVII.

[12] Macrides, “Kinship by Arrangement”, 112.

[13] Macrides, “Kinship by Arrangement”, 112.

[14] Macrides, “Kinship by Arrangement”, 112.

[15] Macrides, “Kinship by Arrangement”, 115.

[16] Ioannis Chatzopoulos, “The Diachronic Evolution of the Institution of Adoption from Greco-Roman antiquity until present”, (PhD diss., Panteion University), 73-74 (in Greek).

[17] Chatzopoulos, “The Diachronic Evolution of the Institution of Adoption”, 73-74.

[18] General State Archives of Aitoloakarnania, Notarial Collection of Mesolongi, F.6.7 #336.