By Carol Kostakos Petranek

In 1981, college student Angelyn Balodimas-Bartolomei sat in the plateia of Pylos, Messinia, and met her Greek family for the first time. As her father introduced her to mostly older relatives, she had no inkling that she would one day become immersed in learning their history. Nor could she conceive that the level of passion it engendered would lead to her distinction of being the first beneficiary of the Greek Ancestry Village History Project Initiative (VHPI) Grant for her work on Family Trees of Pylos, found on Tribal Pages and on this website. Follow her work on the corresponding Family Trees of Pylos-Nestoras Facebook page.

Although Angelyn and her Italian husband, Paul, travel regularly to Greece and Italy, it was not until 2007 that her research began in earnest. Desiring Greek citizenship and learning that she needed to be registered in her municipality, she traveled back to Pylos and began learning about the citizenship procedures. After acquiring Greek citizenship, the following year, Angelyn continued to travel back and forth to Greece for visits and also to lead tours throughout Greece and the Greek islands for the Museum of Natural Science of New York. In 2012, Angelyn & Paul’s oldest daughter discovered the Family History Library in Salt Lake City and uncovered several family documents from Italy. This sparked both her and Paul’s interest in genealogy and from that point on, most of their trips to Greece and Italy were centered around finding out more about their ancestries.

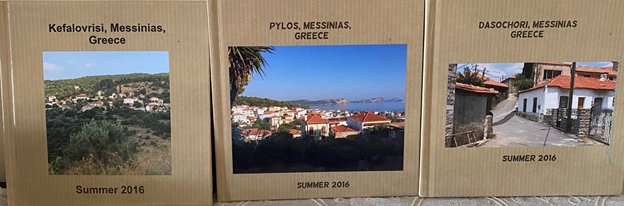

Angelyn’s enthusiasm grew especially as she saw family names written in Mitroon Arrenon, Dimotologion, and church books in different villages and met with priests and civil authorities. She clearly remembers when a priest in her mother’s village of Kefalovrisi (Messinia), exclaimed with delight that she was the first person to show interest in learning the story of her family. Her newly acquainted cousin, Pericles, who was the president of that village allowed her access to an old metal cabinet in the village church which held old documents and birth-marriage-death volumes which she was permitted to photograph. Once back in the States, selected records and travel photos were turned into small picture books which Angelyn freely gave to the many people who helped her.

Understanding the history of a village through its records is crucial to Angelyn’s understanding of her ancestors. As she examines documents she asks, “what was happening in Greece during this year?”

“I have lived in the past through these records,” she remarked. “When looking at the official books, you learn of hardships. You see families who lose several children—one lost 9. I found that my father’s family had several sons named Ilias,” denoting that successive boys named after each other had died. “People will not mention the babies who died, and they are not included on family trees—they are forgotten.” Angelyn described how she came to understand a long-running argument between her father and his brother over their birth years after finding their entries in the Mitroon Arrenon. “There are discrepancies in the records,” she explained. “And we are missing the women from most documents which makes it very difficult to determine the members of a family.”

Citing their order of importance in building a family tree, Angelyn begins with the Mitroon Arrenon and death records, then marriages and births (civil and church). She has used GAK records (General State Archives of Greece), school records, election (voter) lists, family trees, and information from newly found DNA cousins. She has begun examining an unusual document from her village church —a list of the deceased that were remembered during the Saturday of Souls. The deceased is named as “son or daughter of” [father and mother] which could yield new family information. “There is a lot out there that we don’t even know about,” she asserted, providing hope for those waiting for new records to surface.

Angelyn has taken DNA tests with the major companies as has her mother. She is making many connections and collaborating closely with her DNA cousin, Gary, in Oregon who has been researching for 60 years, and who had recorded stories of elders in Pylos before they died. She also is fortunate in having her cousins Toula and Anna in Pylos helping her obtain documents along with Efterpi and Angeliki in Athens who were originally from Dasohori. She is finding that endogamy is posing challenges, but having her mother’s DNA is important as it brings the matches one generation closer to a common ancestor.

Greek Ancestry has donated 3 DNA kits to Dr. Balodimas to help her test more people in Pylos in summer 2021!

A village history project—documenting the village families and their histories–can naturally emerge as one’s research expands beyond a specific surname. It can also be a deliberate and expansive goal. Asked what counsel she would give to those interested in starting a village history, Angelyn listed the following:

- Document as much as you can now. Go to the elders within your own family. Record them now; once they’re gone, their history is gone, as are so many beautiful stories they could have shared.

- Family photos. Make sure names are written and learn the stories behind the photos.

- When you talk with elders and ask them, “what do you know about the family,” they will say they don’t know anything. It is better to ask a specific question such as “tell me about your mother.”

- Be prepared for surprises as you uncover information. Sometimes there are family secrets which people will not want revealed. Be sensitive and respectful.

- Use DNA to meet new “cousins” and to collaborate on research.

- Sometimes people (especially older) may not understand your interest and make comments like, “Why are you doing this? Why do you care about these people, they are dead.” Paul [her husband who is also a family historian] responds with “I love my father, he loved his father, and his father loved his father. I love my family and I have to keep this going.” Then they understand.

Angelyn is a professor in the School of Education at North Park University – Chicago and coordinator of the ESL/Bilingual Teachers Endorsement and MALLC programs. She has incorporated genealogy into her classes and many of her students become interested in starting their own family projects. “Young people want to find out their family. Many are already ‘tied” to their ancestral countries, however for others it is a completely new experience. It’s such a blessing to bring young people in and get them involved,” she says.

Angelyn is planning on using her sabbatical leave to spend extended time in Messinia to pursue her village history project full-time. We applaud her dedication and vision; and we will cheer as her work expands. Congratulations!

Bio

Dr. Angelyn Balodimas-Bartolomei is a professor in the School of Education at North Park University – Chicago and coordinator of the ESL/Bilingual Teachers Endorsement and MALLC programs. In both Greece and America, she earned degrees in Greek Studies & Social Work; Greek pedagogy; Linguistics/ESL; and Comparative International Education & Policy Studies. Having received numerous grants, Angie has performed extensive studies on Greek and Italian Americans, Southern Italian Griki, Greek Romaniote Jews, and the endangered Colognoro dialect of Tuscany. She has also examined Holocaust education in Greece, Anti-mafia education, Italian images in foreign language textbooks and Italian American statue makers. Her latest work focuses on the upcoming series of Greek communities of Europe and Greek genealogy highlighting her three ancestral villages of Pylos, Dasohori & Kefalovrisi-all in Messinia, Peloponnese Greece.

About the VHPI

Announced in the last session of the International Greek Ancestry Conference, the VHPI aims at helping people connect and exchange information by fostering collaboration. A village history project focuses beyond a specific surname to include all identifiable people residing in a specific village for an extended period of time. It includes all projects — whether they are in the planning stage, have commenced, or are completed. In the past two months, 18 projects were admitted into the VHPI! All projects admitted are listed on VHPI’s register, so that people are informed and encouraged to launch projects of their own! Along with publicity, VHPI projects are eligible for major discounts on all Greek Ancestry records and, most importantly, are considered for a VHPI grant. These grants are funded by revenue from the Greek Genealogy Guide and include donations of books, DNA tests, subscriptions to genealogy platforms, as well as other types of support. Their beneficiaries are chosen on a quarterly basis.